In the late 1990s, people around the world began to live in a state of rising fear of two missing numbers.

The computer bug known as Y2K threatened to wreak havoc on the global infrastructure through the tiniest of details: computers being programmed to represent years in two digits (“99”) instead of four (“1999”). Headlines warned that systems would go haywire — crashing planes, freeing prisoners, and potentially leading to “The End of the World as We Know It?” as a 1999 Time Magazine cover posed.

We laugh at Y2K today like it was just another Skidz-like ‘90s fad, but that’s only because computer scientists successfully fixed the bug. (The immovable deadline helped: computer scientists had raised alarm over this exact issue since the 1950s but it took until basically the night before for anyone in charge to do something about it.)

Though it has yet to make headlines, our world today faces even greater threats — also because of incomplete information. The kinds of things alarmist Y2K articles warned about are actually happening right now because of it. The problem in our case isn’t some faulty code. It’s a critical, out-dated assumption.

In the interests of self-interest

Our story begins — where else? — with the origins of capitalism and Adam Smith’s famous observation:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.”

On this point, Adam Smith was absolutely right. Expecting and encouraging people to act out of their own self-interest will produce better results than imploring them to do something for some other cause, however noble. When it comes to capturing what’s actually in our self-interest, however, this observation inadvertently inspired significant harm.

Over the course of the 20th century, society’s concept of self-interest became more and more bound to our short-term individualistic desires. Self-interest is instant gratification — what you as an individual want right now. The wave of consumerist individualism began with the Baby Boomers (leading to the so-called “Me Decade” of the ‘80s) and Millennials are the predictable sequel.

This shift is more than a media fiction. We can track the rise in individualism in everything from the increase of singular pronouns versus collective pronouns in song lyrics to the decline of bowling leagues to the personalized feeds we spend hours in today. Our lives are becoming more atomized and our future timelines are shortening.

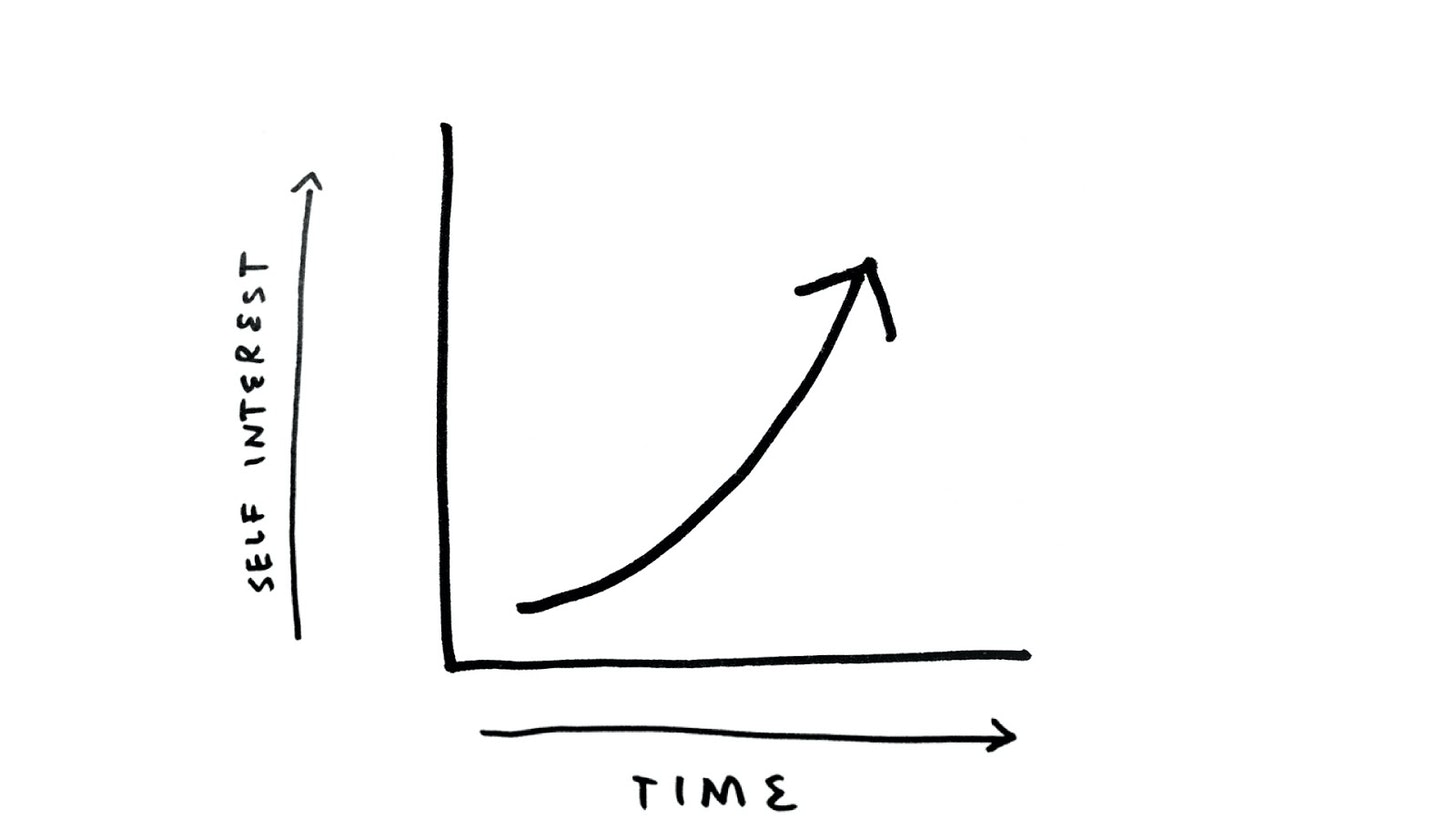

Our view of self-interest has become so specific it even has a logo: the hockey stick graph. A chart where whatever we want — money, power, followers — is growing so fast the line slopes up and to the right.

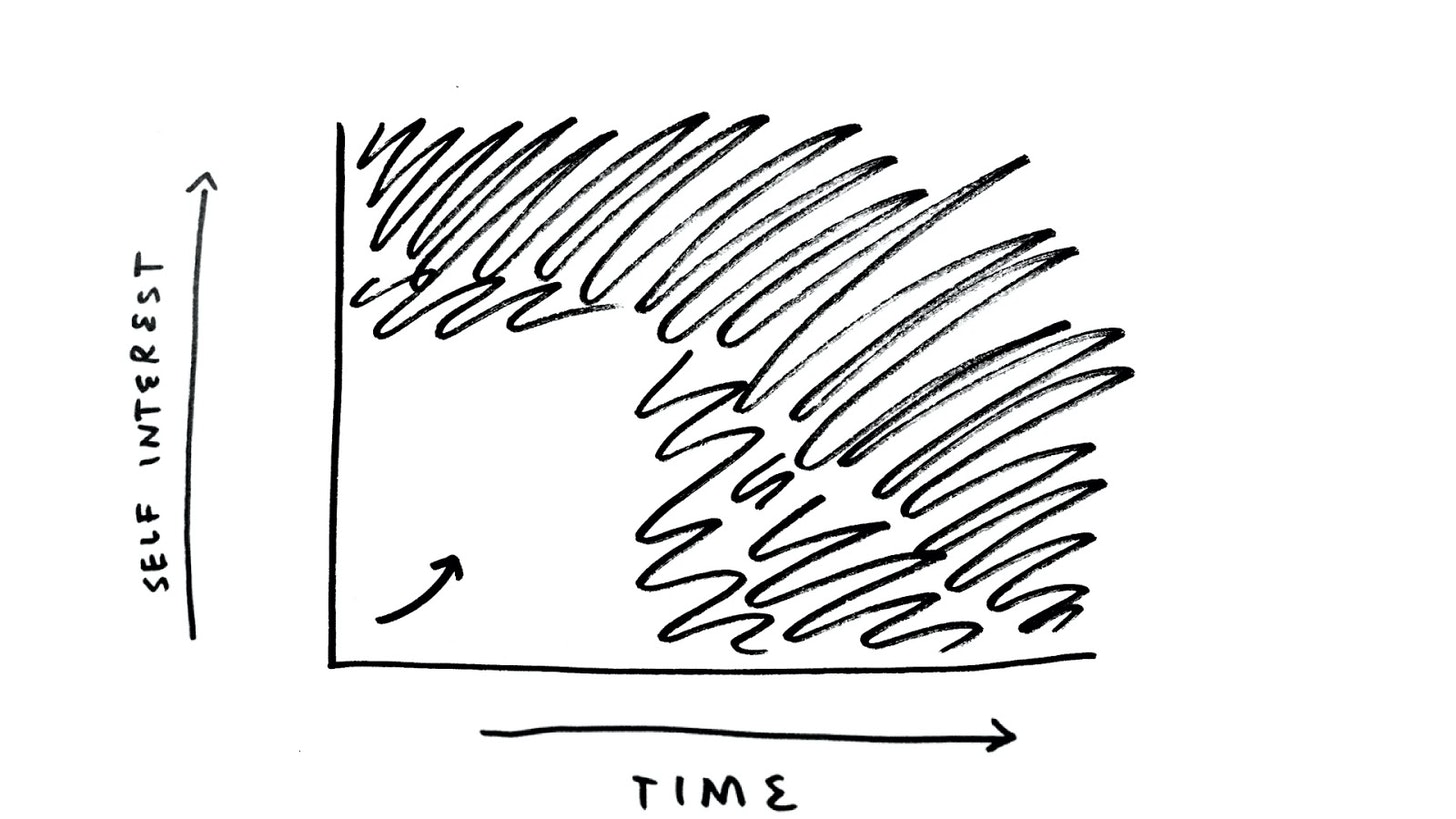

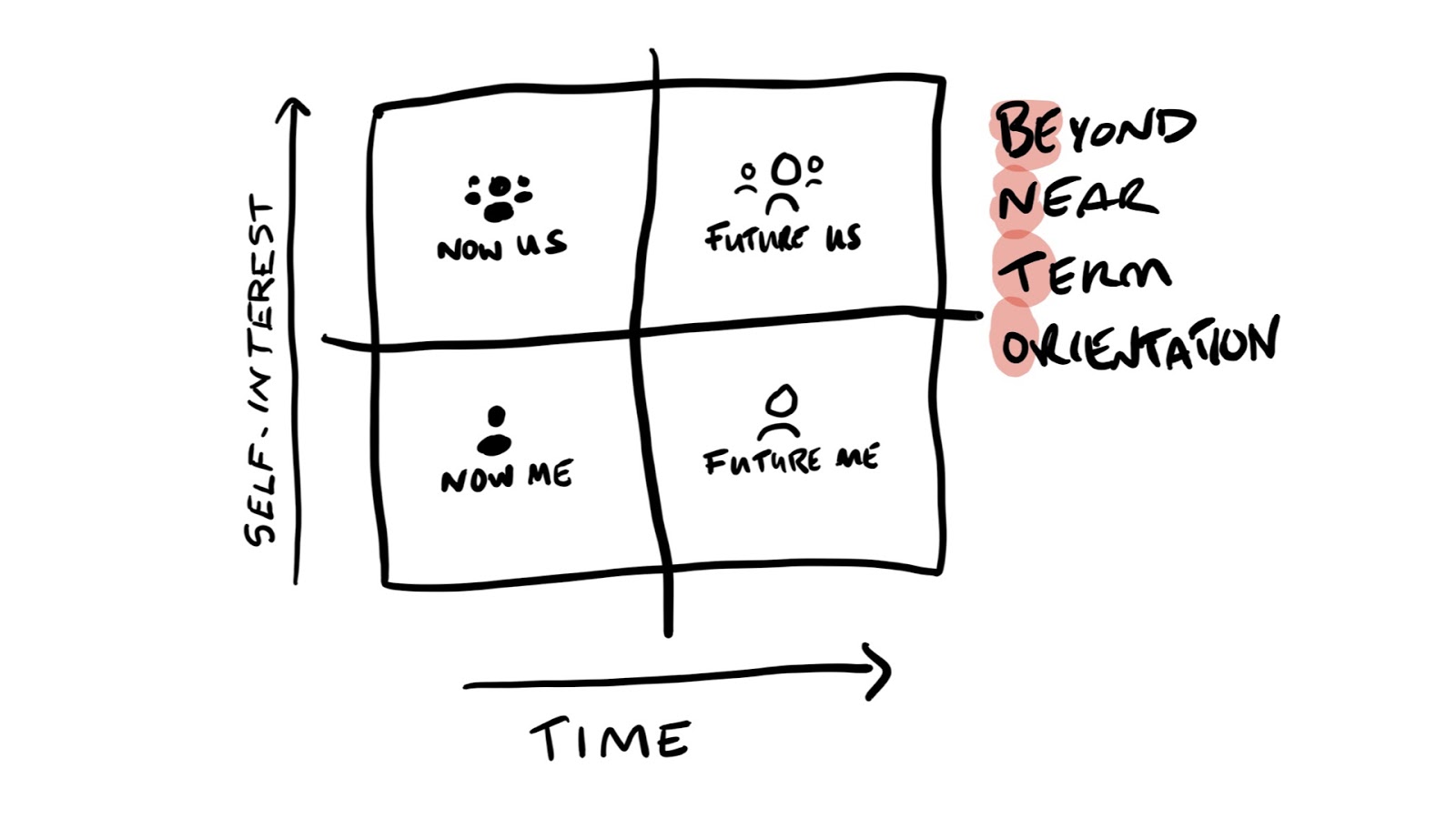

We’ve convinced ourselves this is life’s best-case scenario. In reality, it’s just a small slice of a much bigger picture. When we extend both axes on the graph, a very different image emerges.

From this, we can map out four distinct spaces of self-interest.

There’s Now Me. What I as an individual want and need right now. This is how we see self-interest today.

There’s also Future Me. What the older, wiser version of you wants you to do. The person you become is defined by your actions in the moment.

There’s Now Us. Your friends and family and the communities you’re a part of. Your decisions directly impact them, just as theirs impact you.

There’s also Future Us. The community you belong to even though you haven’t met the people in it yet. Your kids, other people’s kids, the older versions of ourselves that face an uncertain future.

All of these spaces are in our self-interest. Not just Now Me. This theory is called Bentoism, an acronym for BEyond Near Term Orientation.

Why Bentoism matters

For decades we’ve operated like Now Me is all there is. We’ve maximized comfort, pleasure, and financial gain while actively avoiding sacrifice of any kind. We’ve kicked so many cans down the road there’s now a giant wall of them that we’re barreling into head-on.

It’s not that there’s no solution. It’s that we keep trying to solve every decision according to the needs of just one piece of the puzzle. Our systems are built on models that see people as individualized consumers that reduce the range of human possibilities down to the optimization of financial value. People have built truly amazing machines to do these things. But while humanity’s Now Me is a giant glimmering skyscraper (with extraordinary amounts of homelessness), its Future Me, Now Us, and Future Us look more like the summer disaster movies we escaped into so we could tune out the bad news our disinterest further fueled.

Despite all of this, I’m optimistic about humanity. I believe people do the best they can with what they have and what they know. The question is what don’t we know, and how can we gain it or become more aware of it?

More clearly defining our self-interest — the playing field we agree on as in-bounds for our decisions — is exactly this kind of awareness adjustment and one that can drive fundamental shifts on both the individual and societal levels.

This would be a big change, but changes of this level happen all the time. They just take time to happen. Thirty years, give or take. In our case, that means working to redefine our map to self-interest by 2050.

Why 2050? Because profound changes in social values happen in generational increments. (In my book I write about how everything from modern medicine to exercise to hip-hop went from nowhere to mainstream in thirty years.) The people leading the world in 2050 will be Millennials and Generations Y, Z, and COVID. Groups with very different ways of seeing the world than those now in charge. A falling empire will give the 2050 generations the unfortunate responsibility and opportunity to lead humanity’s most dramatic evolution in more than a century.

The overwhelming majority of these people recognize our current path is a dead end. What they lack is a vision for what to build instead. The bento is a map to our new world.

Creating new systems and refactoring existing ones to reflect this new map is critical work. Here’s how I described it in my book, which closes with a snapshot from a sci-fi future:

“In 2050 a Bentoist view of value is a real thing. People better understand their values and live more self-coherent lives. Companies hold themselves accountable to a wider set of values that they take as seriously as their profitability. Slowly but surely over the course of thirty years, a belief in rational value beyond financial value becomes normal.

“As the Bentoist approach to value emerges, talented people become drawn to its unique challenges. Using your skills to maximize financial value seems like a waste when a whole new frontier of value awaits.”

A year into the journey, this vision is starting to become real.

The Bento Society

Over the past year, Bentoism has become more than a theory. It’s become a community of people and a laboratory for experimentation. Its name is the Bento Society.

The Bento Society hosted more than 100 workshops for thousands of people from around the world this year, it's first. One member, Julian, describes it as "a welcoming space for people to rejuvenate themselves and co-imagine the world together."

In these sessions, people actively confront and adjust how their beliefs, values, and lives come together. They push at the boundaries of their self-interest. Here’s what members say about it:

“Ever since I created my first bento, I knew this was the community and space for me because I feel like I'm contributing to something bigger than myself. I consistently leave our time together feeling refreshed and motivated for the week ahead. Bentoism has simply beautified my life, inside and out.”

“It's helped me feel more confident and less alone when looking at the current state of the world and less stuck about certain decisions.”

“It literally changed my life. I feel like now I have a focus beyond the present. It makes me think beyond today and see life from another perspective.”

“It’s given me lots of clarity and a great framework to make important decisions that I struggle with. The interactions I’ve had during bento events have been super meaningful!”

“Bento has helped me realize that I'm not yet very clear about what kind of future image I have of myself and the society I want to live in. Bento is currently helping me to interpret this nebulous image of Future Us and Future Me and to adapt my current actions accordingly.”

“I am conscious of what I am creating in a holistic sense I am connected with the reality around me and by default am contributing sustainably. This ‘feeling a part of the whole’ is comforting and cleansing at the same time.”

“Being able to sit and really think about and be accountable to all aspects of my now and future selves is time I now treasure in my week. Maybe changing the world is in how we all live our lives and not the preserve of a select few.”

“Bentoism helped me begin to unearth the broader sense of values that I have that exist outside of commercial consumerism and my existence being defined by my daily career.”

Bento Society members come from all around the world and every walk of life. We are retail workers and artists. Students and professors. CEOs and customer service workers. Health care workers and filmmakers. Scientists and Uber drivers.

The Bento Society’s Mission

As important and life-changing as this work is, the goal of Bentoism isn’t just to help people better see what’s valuable and in their self-interest. The Bento Society’s mission is to redefine what the world sees as valuable and in its self-interest. Our goal is for this perspective to become the new default.

There are three parts to our work:

1. Teach people Bentoism and create a welcoming space where they can practice, explore, and create self-coherence.

We do this now with our Weekly Bento on Sundays, smaller Group Bentos on Wednesdays, a Slack community of several hundred people, and in newsletters to a couple of thousand people. This work will grow and evolve to make the bento as useful and accessible as possible.

2. Introduce Bentoism to organizations, community groups, and other collective structures through existing members.

The next phase is the adoption of the bento as a decision-making and priority-setting tool in organizations. The new Bentoism website has a section devoted to this with real world examples. The goal is to equip Bento Society members to shift their own organization’s maps in Bentoish directions.

3. Lead, fund, and support projects that establish a wider map to value and self-interest.

We're heavily inspired by Thomas Kuhn's idea of "normal science." That in the wake of paradigm change, new ideas become useful once the process of "normal science" happens. Kuhn defines normal science as the iterative, “puzzle-solving” work of applying a theory to individual fields of study. As individual scientists run experiments across a variety of contexts we learn how the new paradigm practically works. What had been a political debate over knowledge becomes practical and factual, and the new paradigm becomes adopted.

The Bento Society plans to push the normal science of defining new values and a larger map to self-interest. This will start with community-supported grants for projects that expand how we define value and self-interest, which we’ll announce later this year. If you’d like to tell us about something you’re working on in this spirit we’d love to hear about it.

A map to the new world

In the lead-up to the year 2000, society became acutely aware of how dependent its systems were on faulty code. The Y2K bug turned what had been invisible and irrelevant into a major part of life.

COVID-19 has similarly made us aware of the flaws in our systems and thinking. Social distrust, the active undermining of collective norms, and a weak public health infrastructure are all the disastrous consequences of decades of under-investment in Now and Future Us. The pandemic has made clear which societies are limited by short-term individualism and which are not.

The societies that are successfully navigating the pandemic are ones that have invested in Now and Future Us. Denmark put their economy and way of life into a temporary freezer at the start of COVID so it could be preserved for unthawing later. New Zealand’s high social trust has resulted in a society essentially free of the virus. In Asia, COVID has been more of a speedbump than a dramatic reset. These are truly developed societies. These are the societies whose maps of the world remain intact.

Struggling nations like the US and UK are lost because their existing map to the world — dominated by the pursuit of financial gain and Now Me desires — has no relevance to where we find ourselves. Economic growth can’t cure disease. Public health can’t be protected in societies led by governments that believe society doesn’t exist. These old maps have even less relevance to the challenges we face in the years and decades to come.

But we can solve this. Shifting how we see self-interest is a scalable solution. It fundamentally changes our relationships to one another without infringing on personal beliefs. It imposes no values beyond an increased awareness of ourselves and each other. Yet it dramatically changes the context and substance of our decisions.

Like Adam Smith’s OG ideas, Bentoism relies on each person looking out for their own self-interest. But it also, in the simplest of ways, expands the perimeter of our self-interest to include each other and our future selves. The bento is a map of our new world.

Linknotes

- The softcover of my book, This Could Be Our Future: A Manifesto for a More Generous World, comes out on November 19 with a new afterword and cover:

- The new Bentoism website offers several useful tools and next steps, including:

Here’s a short video walkthrough of the new site:

- This post makes two references to defining new values without explaining what’s meant by that. I’m going to write a separate post about this aspect later, but a quick summary:

If the bento is a map to what’s in our self-interest, then it’s also a map to what’s valuable. The same tools and measurements we’ve used to grow and measure financial value can be applied to non-financial values that exist in other dimensions of the bento. Loyalty, social connectedness, human wellbeing, purpose, and others are values we’ll learn to define and measure as a means to scalably make decisions and distribute goods based on non-financial values. Adele distributing concert tickets using a loyalty algorithm, which I write about in the book, is one example of what I think of as a post-capitalist transaction. The past newsletter Post-Capitalism for Realists explores this as well.

-

People and ideas who’ve inspired this work: Michael Walzer (Spheres of Justice), Elizabeth Anderson (Value in Ethics and Economics), Donella Meadows (Limits to Growth and Places to Intervene in a System), Frederich Laloux (Rethinking Organizations), Mariana Mazzucato (The Value of Everything), the principles of Weight Watchers and Alcoholics Anonymous, EF Schumacher (Small Is Beautiful), and Thomas Kuhn (Structure of Scientific Revolutions).

-

A huge thanks to Jamie Kim, Justin Kazmark, Ian Hogarth, Frederich Laloux, Emily Ludolph, Toby Shorin, Flo Buhringer, Mario Vasilescu, Evan Adams, Anne Muhlethaler, Julian Cohen, Yuki Nakamura, Rhys Lindmark, Laurel Schwulst, and Taichi Aritomo for their help with this essay and Bentoism, and of course everyone in the Bento Society.

-

One year ago this week my book came out. I spent a lot of the year worried whether if it was doing well enough, seeking affirmation and not knowing how to feel. Looking at the state of things now, I couldn’t be prouder of how this has unfolded. So much of that is because of the community of people who keep coming together around these ideas. My deepest thanks to all of you.

Peace and love my friends,

Yancey

The Bento Society