Recently I was on the road giving talks and workshops around my book. During my travels I met with a number of CEOs, investors, and other business leaders, and in many of these meetings climate change came up.

Some of these conversations turned into awkward exchanges not far from the one I had with the outdoors CEO. Others were more like-minded. In most conversations I heard some variation of three themes:

- The desire for “market-based solutions” to climate change

- The belief that “state-based solutions” would be a bad thing

- Admission that few companies (including their own) were doing much about it

Not exactly the Venn Diagram you’d like when the need to reduce emissions is so acute, but, alas, it’s where we appear to be.

Even in the moment this set of constraints felt contradictory, not to mention a convenient defense for business as usual. Which isn’t at all surprising since that’s pretty much everyone’s position on the climate if we’re honest.

Underneath the deflection, though, I felt a kernel of truth in these themes. I think what these people were trying to say was that they wanted a solution to emerge through a process of competition. What they couldn’t imagine is what that competition would look like, or why they’d want to participate in it.

What could a competition supporting the climate look like?

Greening up with the Joneses

Last year the nonprofit Omidyar Network explored the question of how to create a “race to the top,” as they put it, to spur higher standards for how companies treat digital identities. They identified several key ingredients, including:

-

A coalition to lead, i.e. more than one participant who will advocate for and work to establish the new standard.

-

Articulation of values, norms, and goals of the race, i.e. defining the challenge and how the coalition will get there.

-

Tools to make participation easier, i.e. the less onerous the path to participating, the larger the pool of people who will join.

We’re seeing several of these “races to the top” right now.

The B-Corporation movement, which encourages companies to meet a higher standard of behavior through a credential (the B-Corp designation) as well as a legal designation that makes non-financial goals core to a company’s legal responsibilities (the Public Benefit Corporation model).

The Climate Neutral project, which gives companies a calculator to analyze the entirety of their annual CO2 emissions, provides a verified carbon offsetting process to balance them, and created a product label to denote companies that take this action. Allbirds, Kickstarter, and Reformation are among the companies that have signed up.

The Center for Humane Technology is (among other things) creating an industry coalition advocating for less addictive technologies, building on the success of the Time Well Spent movement which resulted in screen time trackers and other awareness-enhancing tools becoming standard on most phones.

Each of these movements fulfills the framework Omidyar laid out. They’re formally organized, there are clearly articulated goals for the changes they’re advocating for, and they provide practical tools for others to get on board.

Today there are almost 10,000 PBCs in the world; in the first two months of 2020 Microsoft, BP, and Starbucks made pledges to go carbon neutral or negative (unrelated to Climate Neutral); and Instagram and other platforms are considering previously unthinkable product changes as a result of public advocacy. In the big picture these things are still small but they often punch above their weight.

These movements combined with employee activism (as we saw at Kickstarter this week — congrats to Kickstarter United) are changing norms. Because most companies consider themselves leaders not followers, this shift in norms is starting to put other forms of value — the importance of all stakeholders not just shareholders, the reduction of CO2 emissions (or at least the appearance of it), and greater mindfulness around the addictive potential of technology products — in their conscious self-interest for the first time.

Rules of the race

The race scenario we most commonly associate with markets is a race to the bottom. A competition where the rewards are finite (and even singular), and the goal for each player is to get as much for themselves as they possibly can. In a race to the bottom things can get pretty Hunger Games pretty quickly (see: online advertising, user data, college admissions, etc).

The race to the top scenario described above similarly uses competition as a motivating force, but the outcomes are very different. In a race to the top, the goal isn’t to gain a zero-sum of value, it’s to, in effect, create as much value as possible regardless of who eventually owns it.

Think about the competition to be the most climate-aware company in a category. The benefits of this “competition” aren’t just enjoyed by the “winner” (if such a thing could be said to exist). They’re enjoyed by everyone. The race itself is likely to inspire others to join. A race to the top isn’t zero-sum, it’s positive-sum.

Might race to the top dynamics be a defining feature of post-capitalism?

By post-capitalism, I mean a world where value isn’t solely defined, distributed, or optimized as financial capital. In post-capitalism, other values — something’s ecological value, its social value, its relational value, and values we’re not aware of yet — will be just as critical depending on the situation.

In a world where capital is less scarce — as our world is becoming, albeit with very unequal distribution — these other forms of value will gradually become as important as financial value. And these are positive-sum values for the most part. One person having that value doesn’t mean another person can’t. It may mean that more people can.

A driving motivation in a capitalist world is for businesses and owners to control the excess financial value created by their operations. In a post-capitalist world these kinds of behaviors would still exist, but there would also be races for new kinds of values and a new willingness to create value without the need to own it.

When Race to the Top > Race to the Bottom = Progress

A race to the top doesn’t stop a race from the bottom from happening. Even as renewable energy usage grows, emissions from fossil fuels are growing too.

And even within a race to the top, there are races to the bottom. Think about companies using greenwashing to claim their products are organic or more environmentally sustainable than they really are. A system that’s optimizing for all the “right” things still creates opportunities for bad actors to take advantage.

This is where the business world position that state-based action would be a bad thing is problematic. Some races, like the race to decarbonize our society, most likely cannot be run solely through markets. We need the state to set the floor for how low the race to the bottom can go. Laws codify the progress that markets and norms make.

Perhaps a plausible path from here to there would start with the business world launching a race to the top to become carbon negative in each industry. If someone like the Business Roundtable led this it would meet the conditions laid out earlier (coalition ready to lead, clear goals of the race, tools to grow participation) and would inspire more companies to follow suit, significantly reducing CO2 emissions. (This is what Climate Neutral is trying to do.) As this process raises the bar for corporate norms, governments could then raise the floor behind them. Better to create change yourself than wait for it to be forced on you.

In a world where many doubt the sincerity of Fortune 500 carbon negative pledges this sounds far-fetched. But even if companies are insincere now, public pressure combined with race to the top dynamics and a more normalized process will steadily raise the bar. It’s this push and pull that ultimately results in progress.

The unseen power of redefining value

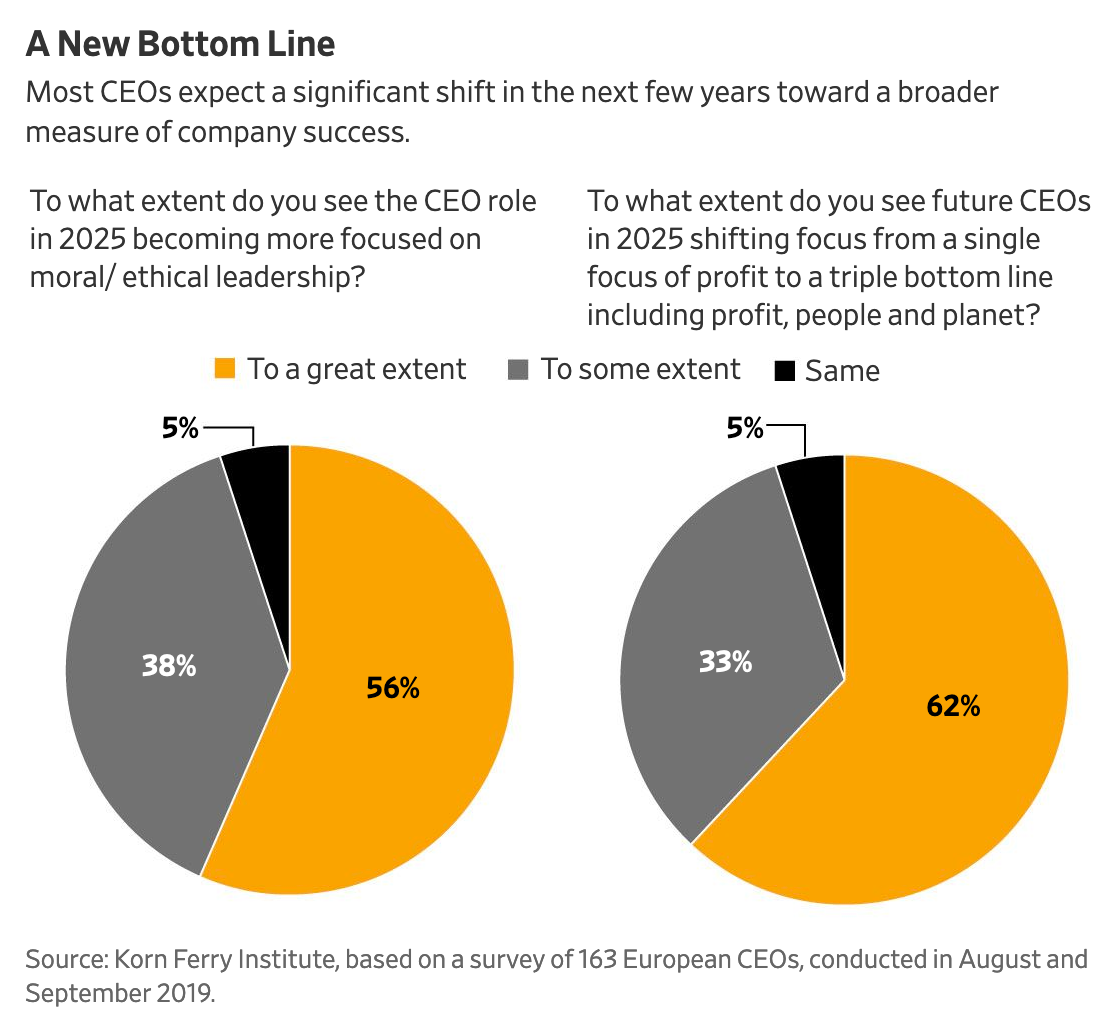

Last year the Wall Street Journal published the results of a survey asking 163 European CEOs whether they thought the responsibilities of their job would change in the next five years when it came to values. 95% of CEOs said it would.

Because of the importance of reputation, brand, and employee and customer trust, businesses are thinking about what’s valuable in new ways. How they view their self-interest is changing with it.

During my travels I met with the CEO of a particularly impactful company regarding the climate, even though their business has little direct interaction with it. I asked the CEO why they were doing it. What was the ROI?

The CEO thought about how to answer.

“The employees really like that we’re doing it, but that’s not the reason,” they said. “It’s good for our image I guess, but that’s not the reason either.”

The CEO trailed off and was quiet.

“Is it just that it’s the right thing to do?” I prodded.

“Yes,” the CEO replied. “I guess that’s probably it.” But I could tell they weren’t sure.

Investing a company’s financial resources into creating collective value without a direct financial return is very unlike the world we’ve been living in. But the reasons and ways of creating value are changing.

The language to justify this new way of thinking feels awkward now because we’re still writing it. But this will also change. And change is contagious. Some people changing means more people will change. If you run the race long enough, the race itself can change too.

Linknotes

-

Donella Meadows, “Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System” — How systems evolve and the importance of norms and values.

-

Scott Alexander (Slate Star Codex), “Meditations on Molloch” — Why no matter how hard we try there will always be a race to the bottom.

-

Tristan Harris and Nicholas Thompson, “Our Minds Have Been Hijacked By Our Phones” — Creating a movement around a new user experience paradigm.

-

The Weekly Bento — A weekly ritual for setting priorities in line with one’s values.

Peace and love my friends,

Yancey

The Bento Society