This is a talk about what happens when a culture is driven by the need for money to make more money.

A simple way to think about this is through real estate. Throughout history it has been advantageous to be a land owner, and today is no different. People make a lot of money buying, developing, and selling land. Even after the crash of 2008, commercial real estate has climbed again.

As investors and developers churn through properties, there’s a significant impact on the communities that actually live and work there. For families and neighborhood businesses, they must significantly increase how much money they make or they have to leave. No matter their importance to their community, they can’t stay if they can’t pay. And few can.

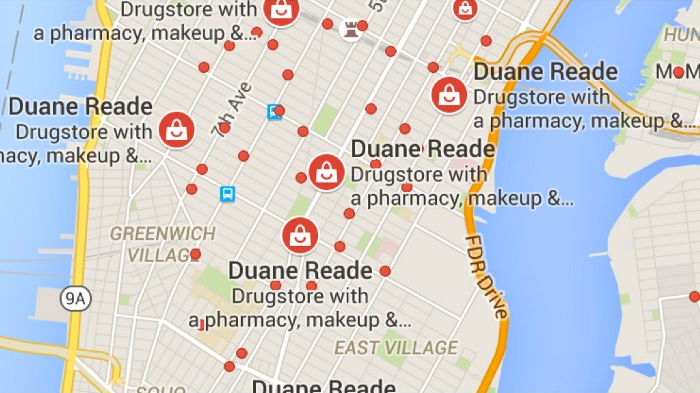

What happens when these businesses leave? New businesses that can maximize how much money they generate move in. And these businesses are, inevitably, chains. Fast food, retail, banks, and others whose operational mantra is based on capital efficiency. Investors make money, franchises notch a new location, and the neighborhood suffers a significant death.

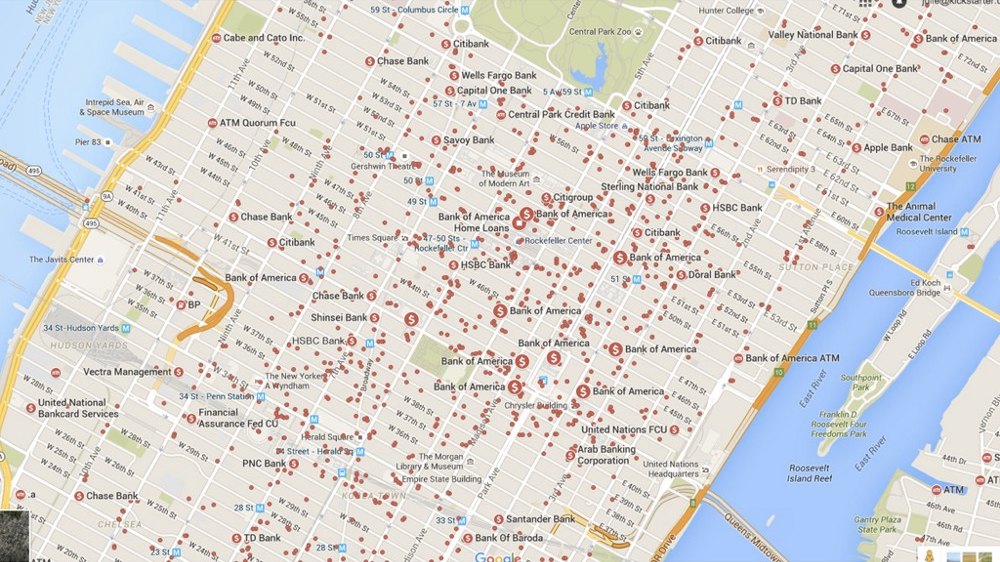

In New York City, many of the businesses that move in are banks. There are more than 1,800 bank branches in New York — 60% more than there were a decade ago.

What happened to the people that were there before? What happens to those neighborhoods now that their communities are gone forever?

This isn’t unique to New York or cities. In the past 30 years, downtowns everywhere have been hollowed out by strip malls, chains, and real estate development. Local businesses that serve their communities are going extinct.

We act as if this is an inevitability. But is it?

Behind this dynamic is a monoculture of money optimizing for more money. An investment mentality that hollows out our culture. Real estate is just one example. It’s happening across many segments of our society. And in each case, the existing community pays the price for the investor’s upside.

There are different forms of this dynamic.

A New York Times investigation found that just 158 families have provided nearly half the funding for presidential campaigns. What better investment than your own politician?

In music, 80% of the concert industry is owned by Ticketmaster. A diverse universe of record labels is steadily consolidating down. A shocking percentage of Top 40 hits are written by four Scandinavian men.

In Hollywood, it’s sequels, prequels, and risk-averse exploitations of existing IP — now in IMAX and 3D!

In tech, many investors’ first question for entrepreneurs is “what’s your exit strategy?” Big rounds, big burn rates, and big valuations push startups in the same direction. Maximize growth so you can eventually maximize money for yourself and somebody else.

When everyone is optimizing for money, the effects on society are horrific. It produces graphs that are up and to the right for all the wrong reasons.

We can’t assume that this will work itself out. As money maximization continues, all of us — and the poor and disempowered especially — face a bleak future. This model is only interested in supporting those that can afford to buy in.

It feels like we’ve been auto-subscribed to a newsletter that’s sending increasingly depressing emails. How do we get off this ride?

Do we stay opted in? Or do we opt out?

If you stay opted in and play the game, the ultimate best case is you’re one of the few that gets rich. Later you can give some money away to charity. But other than your bank account, little has changed. The existing structure is reinforced.

Do we opt out? Imagining opting out is emotionally satisfying.

“I might delete Facebook today.”

“I’ll go back to my Razr phone.”

“Maybe I’ll try homesteading.”

But to do any of these means becoming a ghost to your community. It’s impractical. Very few of us ever follow through.

Is there a third option? I think so. I don’t have a fully-fledged plan, but I have some thoughts on where we can start.

Number 1: Don’t sell out.

At some point in the past ten years, selling out lost its stigma. I come from the Kurt Cobain/“corporate rock still sucks” school where selling out was the worst thing you could ever do. We should return to that.

Don’t sell out your values, don’t sell out your community, don’t sell out the long term for the short term. Do something because you believe it’s wonderful and beneficial, not to get rich.

And — very important — if you plan to do something on an ongoing basis, ensure its sustainability. This means your work must support your operations and you don’t try to grow beyond that without careful planning. If you do those things you can easily maintain your independence.

Number 2: Be idealistic.

Always act with integrity. Really be clear about the things that drive you. Remember the lessons your parents and grandparents taught you about how to treat people and make sure your business lives up to that.

Don’t sink into the morass of “industry standards.” Don’t succumb to the inertia of the status quo. Don’t stop exploring new ideas. A small number of people can change how society works. It’s happened before and it will happen again.

There are some great examples to look to for inspiration.

Patagonia is a Benefit Corporation that will share proprietary information with competitors if it will help the environment.

REI is a co-op that announced they’re closed on Black Friday and they’re encouraging their employees to “opt-outside” instead.

Basecamp and the Hype Machine are independent software companies that put their products and life experience ahead of creating massive growth curves. Ten years in and they’re independent and going strong.

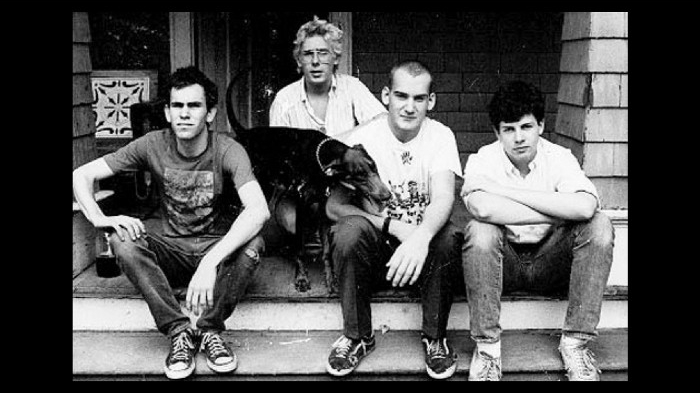

Another inspiration is Fugazi and their label, Dischord Records. From playing all-ages $5 shows to running an independent label for 30 years, we can recontextualize them as entrepreneurial heroes. Look at that photo — that could be a founding tech team. There’s even an office dog!

What these businesses have in common is that they are clear on their purpose and they follow a strict code in its pursuit. They don’t want to be everything to everybody. They just want to be themselves.

This thinking is very contrary to the current business zeitgeist, which is all about aggression and being big and fast. Everyone wants to be Napoleon. And we all know how that turned out.

Look at the language on that cover: “be paranoid,” “go to war.” Its violence suggests that being ruthless is the only way to survive. We hear this all around us.

When I became the CEO of Kickstarter two years ago, this tone created a crisis for me. I had never approached my work as something to be done aggressively, but with the weight of the new job and those external voices on my shoulders, I suddenly had doubts. Is that who I needed to be as CEO? Everywhere I looked I saw messages of anxiety and fear. I questioned my instincts and who I was as a person.

Then I read Not For Bread Alone. Konosuke Matsushita ran a company in Japan for many years with a clear ethos. His philosophy was to always act creatively and with integrity, to pursue a positive impact on society, and to encourage collaboration among his team. It’s an ethos that’s as right today as it was then. It confirmed that I didn’t have to play the fear game.

Approaching your work with thoughtfulness at the core is challenging. You’re going against the grain. Your tools of measurement are very different from your peers. It’s easy to doubt yourself — I do it all the time.

But in more important ways, it’s so much easier. You’re free to act with conviction. You can say and do what you believe is right. Your principles will still be tested, but you can respond in ways that will make you, your community, and your family proud.

It’s not about conquering the world, it’s about doing the right thing. When done correctly, this creates the ultimate product-market fit.

Community supported agriculture is a great example of this. A farm produces its crop for a community of people who receive the bounty every week. The value created and shared is balanced.

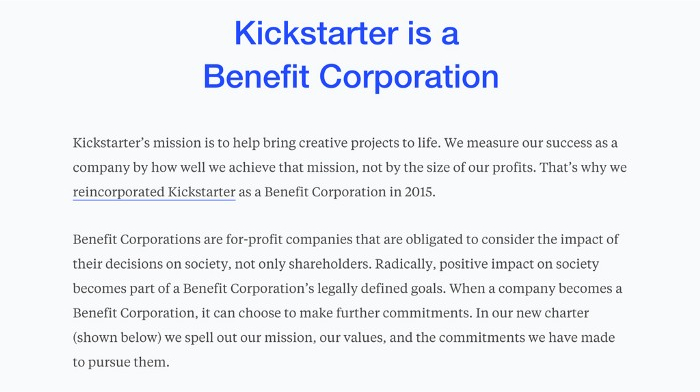

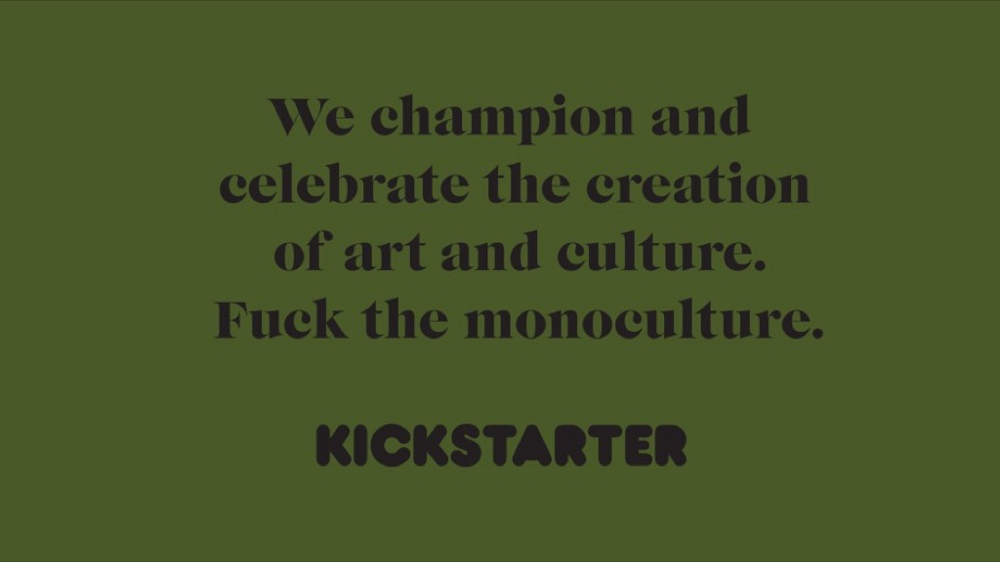

We want Kickstarter to be similarly in sync with society. Earlier this year we became a Public Benefit Corporation. This means we are legally obligated to consider the impact of our decisions on society, not just our shareholders. Though we are still a for-profit company, as a PBC it’s very different from the expectation that for profit companies maximize shareholder value above all. It acknowledges and embraces that you are a part of a larger community.

We don’t expect everyone doing a Kickstarter project to become a Public Benefit Corporation, or to even care. We want artists and creators to be able to create and build for their own reasons. No single mentality is forced on anyone. It’s a polyculture of aspirations and motivations — just as it should be.

Walking around NYC and seeing a bank on every corner is depressing, but the monoculture’s reign is impermanent. As more of us challenge the status quo, change will spark and spread. The hollowness and corruption of the pursuit of profit above all is obvious to even those who practice it. A new approach founded on a diversity of thought and experience can and will thrive.

I don’t know what the exact right steps are to change all of this. This is just me thinking out loud about something that doesn’t get talked about enough. My hope in sharing it is that someone here can build on these ideas, and make them even better. Ultimately this is going to have to be a group effort.

But we want to be very clear on where we at Kickstarter stand on this. Internally we have a Mission & Philosophy handbook that was written by our founder, Perry Chen. Its final page says it all:

Thanks for your time and for listening,

Yancey

The Bento Society