Interviewee: Kate Raworth

Background: Author of Doughnut Economics, Oxford economist

Subject: The century of natural data

Listen: On the web, Apple, Spotify, RSS

“This is the century of natural data. We've got data that no generation before has had, so it would be really weird, in my mind, to say let’s take this incredibly rich data and flatten it in something called GDP invented in the 1930s” — Kate Raworth

Sup y’all, and welcome to the Ideaspace.

One of the most powerful new ideas of this century has an unexpectedly silly name. Called Doughnut Economics, it’s an actionable framework that lays out how both humanity and our planet can thrive in the 21st century.

The Doughnut is already being used in governments around the world — the city of Amsterdam is one example — to rethink and redesign their vision for societal success.

The creator of Doughnut Economics is Kate Raworth, an Oxford economist who now spends part of her time helping others implement the model in the real world.

Last week I had the great fortune to speak with Kate about her work. As two food-based metaphorists exploring alternative models, we connected on many levels. And I was surprised to find Kate asking me almost as many questions as I asked her. This led to a remarkable conversation where, as she put it, the Doughnut met the Bento and the Bento met the Doughnut.

Listen to our conversation on the web, Apple, or (link: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5RRRIR6hXySqmdWxbIfPoy?si=-WpnsO97RgiFSNL5RY1HJA text: Spotify. The full transcript is below.

YANCEY: There’s a great Tweet triptych of you and Mariana Mazzucato and Stephanie Kelton holding each other's books. The three of you have really pushed the Western consensus on economics, the purpose of the state, and the underlying assumptions about money. I would add Carlota Perez and Elizabeth Anderson to that list, two people I also admire. Why are your ideas and this community of voices connecting to this moment?

KATE: So first, let me say that it was really fun to make that little triptych of photos. It was prompted by the fact that Mariana had her book Mission Economy coming out. I had a copy of her book and Stephanie's book [The Debt Myth], and I wrote to them, started a little conversation on Twitter, and said, “Should we just do this thing where we each hold up each other's books?” It was really nice to put that together, then tweet it out.

What I really like about doing that is that that doesn't mean that we agree with each other on absolutely everything. There is not 100% overlap of ideas. But being able to celebrate these ideas—certainly both of their work really helps me rethink parts of economics that I hadn't seen, and helps take away some of the very 20th-Century thinking that we're all taught. Whether it's “Do you know how finance is really designed, and how government money really works?” Or: “Do you realize how much you've been blindsided by the narrative about the market and the state?”

The three of us and indeed others, like Carlota Perez, are pulling away false propositions and myths and diagrams and narratives that don't deserve to stand there anymore. I really like standing in solidarity with new economic thinkers—some of them are women, some of them are people of color, some of them are men—but a lot of people whose work has overlaps. It doesn't mean it all fits together in one neat little jigsaw puzzle. We're all figuring this stuff out from slightly different positions. I like holding that tension and celebrating it.

YANCEY: For a long time it felt hard to find real alternative theories for how else might we explain the world. Now it feels very different. I recently re-read the first Doughnut Economics paper for Oxfam. I've read the book as well, but I was really impressed going back to the paper. The clarity of thinking, how specific the boundaries and the measures are that you talk about—it’s a very whole idea. It's both a significant conceptual shift and also a very specific proposal. When you were writing it, did you feel that clarity? What was that environment you were publishing into? Can you think back to those moments?

KATE: Actually I looked back over that paper the other day as well. What I noticed—it’s something similar to what you're saying—is that I would still put it like that: the core ideas, the core intention, the core examples. I was struck by that. I didn't at all think, “Oh, I would never have written it like that now.”

I was an economics student in the early 1990s, and then walked away from economics very frustrated because it didn't deal with or give respect to the issues I cared most about, like the integrity of the environment, like social justice issues. When I was working at Oxfam I found myself working on economic issues, but we never did it as economics. We did it as social justice, as campaigning against environmental degradation, climate change, for workers’ rights.

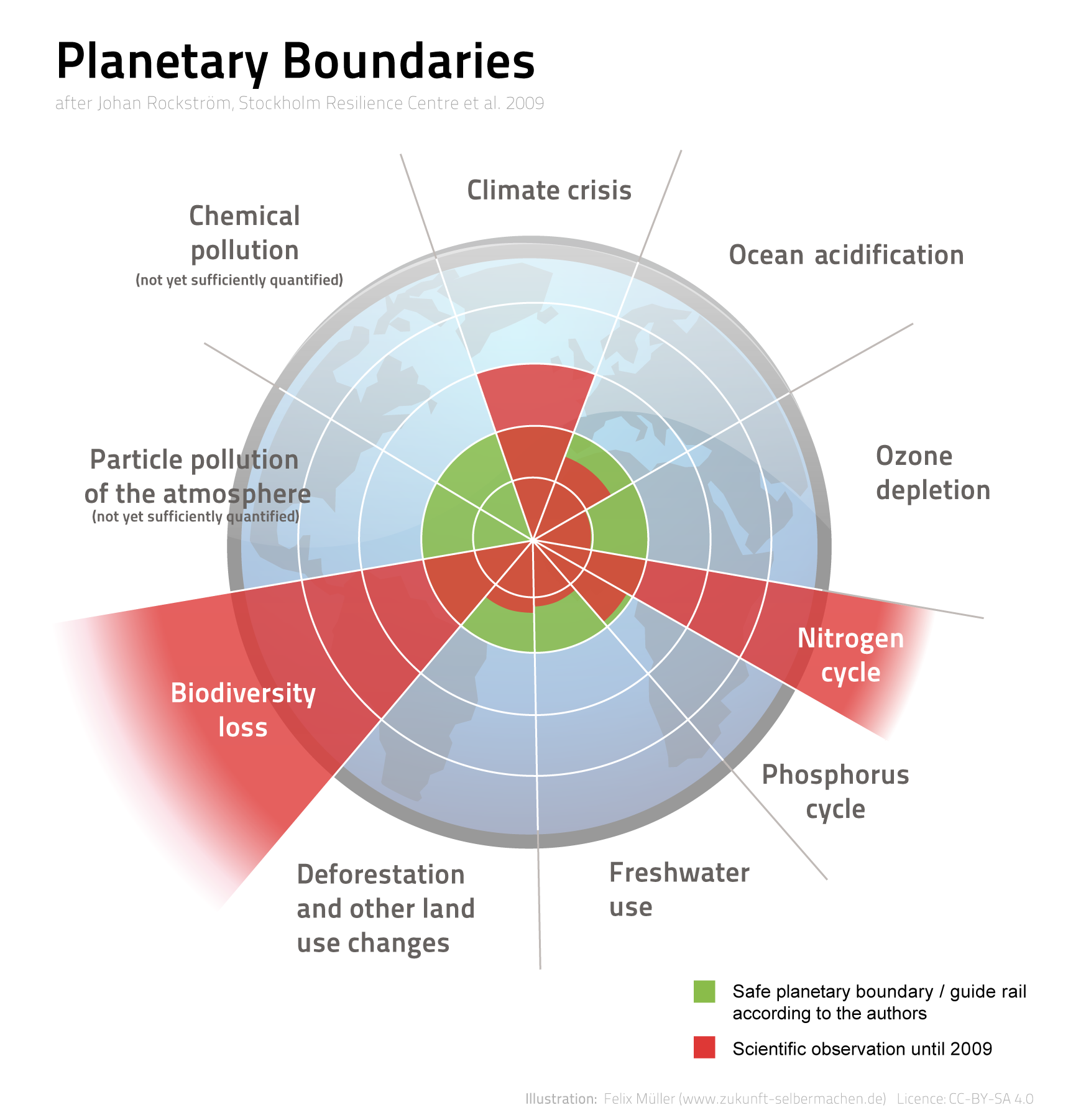

Then I went on maternity leave. I had twins. I spent a year immersed in the care economy. I came back to work, and a colleague of mine showed me this diagram and said, “Here’s one of the things that's been happening while you were away.” This diagram of the nine planetary boundaries had been published by leading Earth system scientists, like you're on rock strong and Will Stephen and about 30 of them. And the picture is this circle, with the picture of the Earth in it, and then these big red lines radiating out, these overshooting lines of warning, of alarm.

The idea was the circle is the safe operating space for humanity. In there we can live well on this planet, living within the means of the planet. But we're in overshoot on climate change and on using too much fertilizer, converting too much land, and biodiversity. I just remember being viscerally struck at my desk by this picture. When I was an economics student, the environment was missing. It was unnamed. It certainly wasn't measured. It was called an externality — the environmental externality. And bang, here it was on the table in front of me.

It's not economists, of course, it's Earth system scientists who put it on the table. I felt like they were throwing down a gauntlet to economists and saying, “Right. Here's the environment. If you won’t put it in your theories, we're going to do it. And by the way, it's not in your metric. This is not in dollars. This is in parts per million of carbon dioxide. This is in tons of nitrogen in fertilizer released. This is in loss of species. These are in nature's metrics.” I was just so excited at my desk. I thought, “This is the beginning of new economics. It's in pictures.”

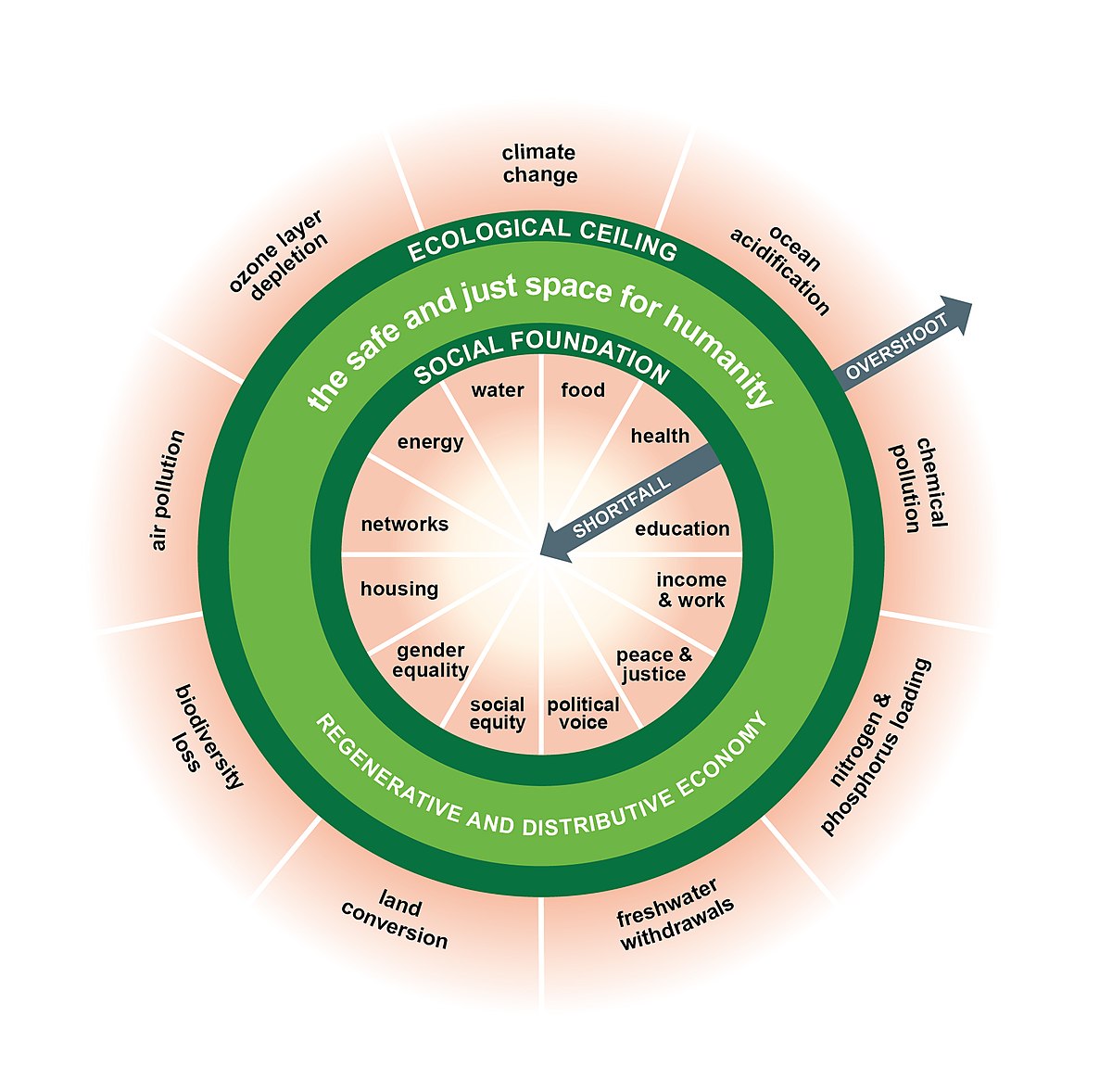

I was literally sitting in this big open plan office in Oxfam. Across the office colleagues were fundraising because of a famine that was a food crisis in the Sahel. People who did not have food, they were campaigning for children's rights to health and education across the world. I remember looking at this circle, thinking: “Hang on, the whole of that circle is not a good space for humanity. It's not like whatever level of Earth's resources we use, everything is safe. Actually, if there's an outer limit of humanity's use of Earth's resources, there's also an inner limit. We've been calling them human rights for many decades since 1948.” So inside their circle I drew a circle in the middle of it. If you don't want to overshoot that outer ring, you also don't want to fall short on the inner ring, because that's people's use of resources for food and water and housing and transport and income. So I had this doughnut-shape picture.

I'll be completely honest with you: I thought, “Well, I like that, because I like representing things in pictures. But [laughs] I don’t want anybody else to see!” And I literally shoved it in the bottom drawer of my desk for about six months. Occasionally I would find myself in conversations about social and environmental things and I’d go, “I've got this picture in the bottom of my desk, that's good, that's useful.” And because my colleague knew I'd been really impacted by the planetary boundaries diagram, he got invited to a workshop with some of these planetary boundary scientists, and he said, “Well, I can't go. Kate, you want to go? You like that picture, you go."

I found myself on the train to Exeter to go to this workshop, thinking, “What am I going to say? I'm not a scientist.” I had this real social scientist/natural scientist insecurity, this classic thing — “they’re the real scientists with their hard numbers.”

I went to this workshop, and very early on in the workshop somebody looked at me across the table and said, “Well, I'm looking at our colleague from Oxfam here, because the problem I have with this planetary boundaries concept is there are no people in it.”

I thought, “Why is this guy staring at me? What is it?” I had in my belly one of those thoughts. You think: “Am I gonna do this?” I hadn't even brought a picture of the diagram with me. But I thought, “I'm going to do this.”

I picked up a whiteboard marker, and I drew it on the wall. “Okay, you drew this outer circle.” I drew it really quickly, because I was slightly embarrassed. “There's an inner circle too, and it's got health and education and food and water.” And, I honestly thought—I’m being totally frank—I honestly thought they’d say, “Yes, yes, sit down. That's nice. But come on. This is science.” But actually, one of the Earth system scientists said, “That's the diagram we've been missing all along. It's not a circle — it's a doughnut.” For the rest of the workshop everybody kept pointing to this diagram on the wall. For me, that was realizing the power of pictures.

It was at that moment this Earth system scientist said, “that's the diagram we've been missing” that I got this fire in my belly. I said, “I'm going to write this up. I'm going to turn this into a paper.” That paper you read just flowed out. It just had a sort of force to itself coming out. I had this conviction because they'd said "that's what we've been missing” and the power of pictures. That was so exciting.

When the paper was launched, so many people said, "I've always thought of sustainable development a bit like this, I’ve just never seen the picture before. This is so helpful.” It made people feel like powerful advocates. It made them feel like they could argue against the idea of endless growth. They could point to this and understand. It put me on the track of thinking about the power of pictures in the visual framing they do. George Lakoff, the cognitive linguist, writes brilliantly about verbal framing: “Are you going to talk about tax relief or tax justice?” Well, this is visual framing. What pictures are we going to put on the table? What pictures are we going to teach the economics students on day one? What do we put at the center of our vision and what do we leave peripheral? That was what inspired me to write the whole of Doughnut Economics through the lens of pictures.

YANCEY: Did you discover the Doughnut? Did it arrive to you? Did it combine in you?

KATE: In that moment I was doodling I had this very strong compulsion. When I saw these planetary boundaries I thought, “That's the natural scientists throwing down the gauntlet to mainstream economics. ‘Here are the boundaries, deal with that.’” I thought, “Here I am. We are social scientists. I'm sitting in Oxfam. What is the rejoinder that can come back from social justice? I need to layer something onto it.” I felt that I was adding. Throwing another hat in the ring, adding something. Once I’d drawn on that circle and figured out the relation, it felt very clear. In that moment it felt like a creation. But of course once I’d drawn it and then reflected—and it took months, even years for some of these things to come clear—of course I can trace it back to things I've seen.

When I was working at the UN in the very late 1990s—so way more than a decade before this happened—I saw this diagram that had been drawn by Friends of the Earth in the Netherlands. They’d drawn these two lines. One was called a social floor and the other was called an environmental ceiling. They’d drawn this idea that there was a space in between that you wanted to be in. I remember seeing this and thinking, “I like that picture.” But there were no metrics, I didn't know what to do with it. I must have filed it in the back of my head. Or rather, it chose to file itself in the back of my head, right? It sits there. These concepts sit there.

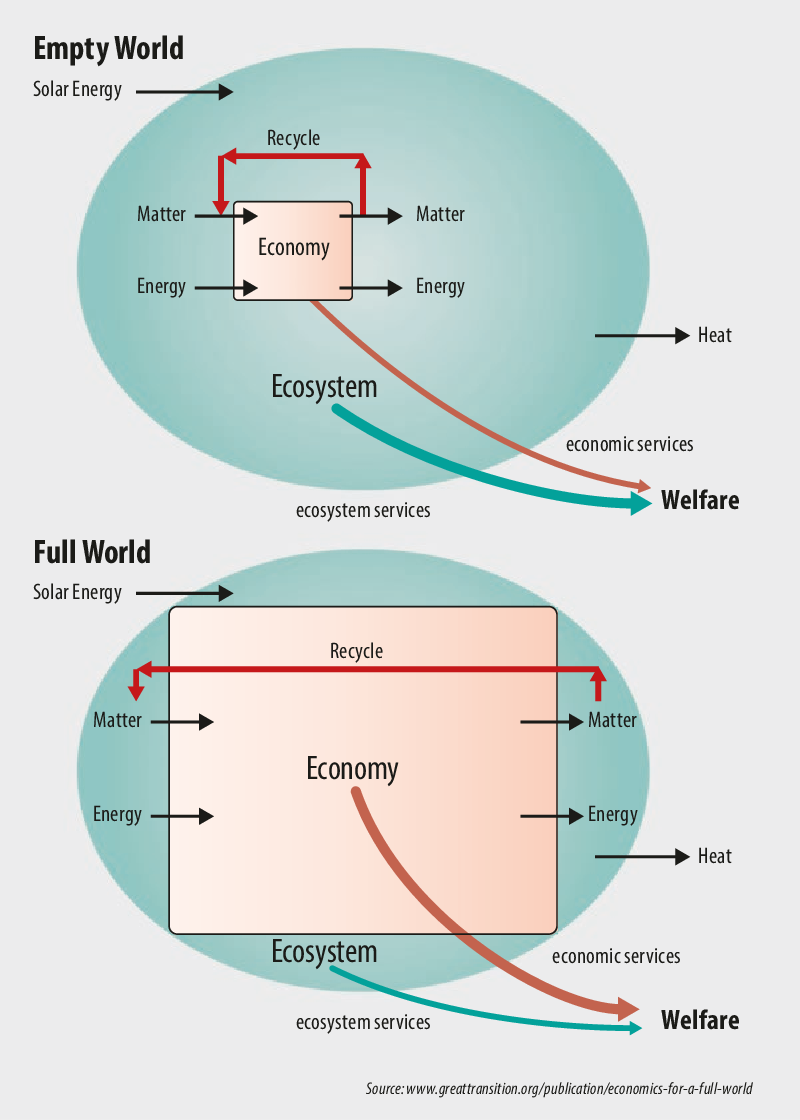

Herman Daly, he's sort of the founding father of ecological economics, drew this amazing diagram that profoundly influenced me as well. Think of two circles and they each have a square inside. In one of them the square is quite small.

He says, “This is the world of 19th- and 20th-Century economics where the square is the economy. It’s quite small, relative to the whole ecosystem. We throw in some materials, we put out waste. It's quite small and the planet’s really big and the sky’s so wide and the ocean’s so deep, it can absorb the things we produce. This is empty world economics. It's fine to go around talking about externalities.

“But actually, we don't live there anymore. We live in the other circle where the square is touching the sides of the circle. In fact, it's almost overshooting the edge of the circle. This is full world. What kind of economics is suitable for full world where we're already banging into the sides of the biosphere?" When I saw that planetary boundaries diagram, it was the square overshooting the circle. It's Herman Daly’s diagram brought to life in metrics.

Also things I'd never heard of. Once the Doughnut diagram was published in that paper you saw in 2012, someone said to me, “Oh, this comes from the ideas of a UK politician called Barbara Ward. Did you know about this?” I said, “No, what did she say?” “Oh, in the 1970s, she made speeches saying, ‘Just as there are outer limits of humanity's pressure on the Earth, so too there are inner limits of what each person can bear.’” So I love your question, where did it come from, did you discover it, create it, find it. These ideas are in the ether. Some of them you've seen or heard, and some of them you've never personally seen or heard, but somehow they keep being transmitted. There's this lovely quote from André Gide: “Everything that needs to be said has already been said, but since nobody was listening it has to be said again.”

Maybe each one of us is a repository for these ideas that we encounter and think, “That's cool, but I don't quite know what to do with that.” We store it and hold it somewhere, or culture holds it. Then it pops up again, this time with doughnuts. Whenever I introduce this concept to the students I teach, I always tell that story. I remember when I was a student, a concept looked like this pristine thing that was just there as an idea that existed. It's important to show that all ideas come from other ideas, and we're influenced consciously or unconsciously by others. That means this idea is just another input into your ideas. So what are you going to create? How are you going to take this journey forward? What's going to come next?

YANCEY: It's almost like the Doughnut has always been true. It has maybe always existed, but it needed to be found, or it needed to be discovered, needed to be conjugated. There's something very beautiful about it. When you first had the idea, this was nine years ago. Over those nine years you had this idea, you wrote a book about it, you've spoken everywhere, you've championed it, now you are implementing it. What's been unexpected? What are the harder moments of this?

KATE: Let me start with the first one, what's been unexpected. Having created this paper at Oxfam—and it had way more resonance and traction than I imagined—I realized that the best piece of advocacy I could do was to leave my role at Oxfam, write a book about it, and allow those ideas to expand more. That's why I wrote Doughnut Economics that was published in 2017. At the time—we’re only in 2021 here, but in 2017—that was very radical. It was edgy and out there.

I spent a couple of years presenting the ideas and following invitations. Always after a talk people would come up to me and say, “I'm a teacher, and I'm actually teaching this in my classroom now, because I think the students deserve to see this and learn this.” “I'm a town councilor, and I'm going to put the Doughnut at the table at the next council meeting.” “I'm a startup entrepreneur. I really want to put these ideas at the heart of my business because, actually, that's why I'm in business. This expresses the purpose of why I've created an enterprise, I'm just using business as a really effective vehicle for doing that.” Or, “I’m a sitting mayor.’ It was really clear that people wanted to do this. And I gradually realized I had to come out of my comfort zone. Having been a researcher at Oxfam, I like ideas. I like researching ideas and drawing. I came out of that and said, “We need to set up an organization that actually enables these people to connect and share.”

That was one of the hardest things for me. [Never having to] think about managing people or money or setting up an organization, just playing with the ideas on a piece of paper, then realizing actually, no, I need to set up something. I waited until I found a co-pilot, because I knew I was never going to do this alone. I met this fantastic Spanish woman called Carlota Sanz. Intuitively, I’d only known her two days and I said, “You know what? Should we do something together?” I just really liked her energy and intention. So we started working together, and it was really clear we didn't want to set up an institute. That sounded far too big and heavy and built in bricks. And so the idea of an Action Lab.

[The Doughnut Economics Action Lab] is about action. It's all about ideas to action. And “lab”: it's light, it's mobile, it's experimental, we’re learning. It has a playful formability about it.

One of the things that surprised me is how much I've enjoyed doing this. I thought I would not want to do that. But actually creating something, and as I'm sure you know through your journey with Kickstarter, it's just a fascinating journey of, how do we create this in the spirit of Doughnut Economics? How do we purpose it? How do we get it financed? How do we design our team? How do we connect with others? And how do we give the ideas away?

We launched a platform, which is doughnuteconomics.org, where anybody can become a member. There are tools all about regenerative and distributive design open for anybody to use and adapt. We just ask that they share back. It's got the principle of reciprocity at the heart of what we're doing.

I'll segue to what you asked me: what's the hardest. It’s not the hardest, but the place where we feel that most could go wrong would be in the space of business. The reason I know that is because some companies have come to me and said, “We love the idea of the Doughnut.” One company said, “We've created our own Doughnut.” And they'd actually taken out the center, which is the social foundation of human rights, and replaced it with business needs. They had the world's needs down the outside and business needs in the middle. I had to say: “You see what you did there? You just took out human rights and put business wants and needs in the middle.” It was totally unintentional. They hadn't intended to co-opt it for their own business purposes. They hadn't seen what was happening because they put their very business mindset at the heart of it rather than asking how business can be in service to this.

Then there were other companies, very big, powerful companies, that would love a cool little tool that would endorse them or make them look good—greenwashing and co-opting. So the place where we're paying most attention is around the way business can use it.

Our current principle is any company is welcome to use it. We’ve actually published a tool on our website called “When Business Meets the Doughnut.” We ask you that you use the whole thing. You look at the design of your company, including how it's owned and financed. You go into questions that might not be comfortable. Also we ask that you use it internally. Because there's a lot of work to do in most businesses. Use it as an internal reflection tool. Don't rush out and put it on your website. Don’t go talk about it. Don't try and associate it with it publicly. That risks turning it into a branding. When we're ready, we'll open up more and engage more with business.

That's this balance we're trying to make between openness and integrity. The hardest thing for me would be if it got greenwashed or co-opted and misused by business in a way that undermined its credibility and value to everybody else who's finding it incredibly valuable.

YANCEY: I'd love to talk about the role of business in society, because I went through the Business Meets the Doughnut tool and watched the video. I’ve written also about the risk of profit motives. When I was CEO of Kickstarter we became a public benefit corporation in part because of this. We wanted to bind our current and future behavior according to a set of principles and values. I was inspired by people like Peter Drucker and Kōnosuke Matsushita, who founded Panasonic, who’d written a lot about the power of a firm with a purpose and clarity in what they do. You have a clear theory of your business. You know what you should do and what you shouldn't do, because the hardest thing for any organization is to stay focused. It’s very easy to get distracted from what’s not core.

In my mind, maybe the most persuasive part of Milton Friedman's idea of shareholder value is this assumption that companies are only going to be good at some things and they’ll be bad at other things. The more focused you are, the more effective you are. There's a tension there between a business, its purpose, and the wider world. How do you think about that interplay? What are your instincts in this area?

KATE: I appreciate what you're saying. Milton Friedman saying the social business of business is to make profit, the business of business of business, as it were. There's a simple clarity to that.

But I'm not sure that we as people lead much of our lives anywhere else like that. Certainly in my family, I’m always, in my mind, juggling more complex things—in terms of my children's welfare, or even where should we go on holiday. There’s multiple factors that we take into account, and that's what we humans learn to do: we balance multiple factors. That doesn't mean there's any one right answer, but we learned to do that. When we drive a car we don't have one dial in front of us where up is good and down is bad. It’s, look at the speed, look at the temperature, look at the revs, what gear you’re in. We learn to do that. We are able to balance multiple considerations to optimize towards a goal. So I wouldn't let business say it's really hard to have a more complex purpose. Of course if you have a really big broad purpose for an enterprise, then, as you said, it could go in many, many, many different directions, and how do we make that choice?

But I also see plenty of enterprises—and I would say, particularly new kinds of enterprises—that are set up with a very clear purpose. And that make sure that they design all of the design features of their organization to be in service to that purpose. And when we engage with any company—and you'll have seen it in the Business Meets the Doughnut tool—we say, “Look, we can talk about what we like about the design of your product, and what it's made from, and the working conditions and supply chains. And that all matters. But what we think is the really deep determinant of whether or not you as an enterprise can be part of a regenerative, distributive future that brings humanity into the Doughnut is the design of your business itself. So let's start with those five design traits, let’s start with purpose. What are you in service to?” I get this from the brilliant corporate analyst, Marjorie Kelly. She says, “Do you have a living purpose?” And you can spot a company with a living purpose because it speaks to something much bigger than itself and recognizes itself: “We’re here to decarbonize energy. We're here to bring health to this community. We’re here to enable change-makers in this space, and we are in service of that. The role we play is this.” As opposed to a very 20th-Century self-regarding company, that might say, “Our purpose is to be the biggest four-by-four manufacturer in Europe,” or something like that.

So having a living purpose. But then anyone can always write something that looks like a living purpose on a website. You can just go and change the code and save the new page and you've got this new purpose. But what matters is that everything else is aligned with actually delivering on that: your networks, your relationship with your customers, and your suppliers and your staff. How do you actually live out the values in that purpose with them, instill it in them, and make sure they hold you to it when times get tough? How do you embody it in your governance: who has voice, who's at the table? The metrics by which you judge the enterprise's success, but also the incentives given to middle management —are those aligned?

And then going deeper, and this is where I think the real power lies: how is your enterprise owned? Because whether it's owned by founding entrepreneurs, or venture capital, or shareholders, or owned by the state, or by employees, or by a seventh-generation family–all of these are prevailing ownership models, they all happen out there—they all have a huge impact on the bottom trait, which is how the company is financed, where that finance is coming from, and what that finance expects and demands. And if it’s shareholders, they will typically want a fast, high return. “Double digits, please, if possible, but nothing too much short of that?” Or is it owned by the employees who say, “The finance is coming in, and we want it to be reinvested in our own conditions and in the duration of our enterprise?”

So where the finance is coming from, but also how profits are therefore distributed. Whether that finance is in service to the purpose or whether actually the purpose ends up serving the finance. For us, it's really key that companies have those deeper design conversations. And then you can say, “Okay, what's our purpose?” The extent to which we align our networks, our governance, and our ownership and our finance—then we can pursue what seems like a more complex purpose. But it becomes very clear whether we are indeed. The way we’re, say, expanding our car sharing club service, are we indeed decarbonizing the energy system? Or are we just growing because we're driven by growth for growth's sake?

I have faith in the human ability to juggle multiple variables and optimize. If we have companies that are aligned to their full design, that purpose can be more complex than simply serving shareholder value.

YANCEY: In the original Doughnut Economics paper, you talk about moving beyond GDP as a core metric of success. And you've written, also about how markets put a price on everything, and they exploit the things that aren't priced. How do you think about addressing this question? Is it about putting prices on things that don't have prices? So we use finance to, say, think differently about the price of a forest? Is it by creating new forms of value that price has to compete with, like other metrics? Is it about tools that limit where the markets can go? How do you think about pushing back against the dominance of price?

KATE: It's a really big one. In conversations about the power of markets and the scope of the market, I often start with: Look, markets are really, really powerful. Adam Smith was onto something; they are a brilliant information mechanism through the price mechanism of coordinating the wants and needs and the offers and the purchases of billions of people who may never talk or meet, but they can coordinate through this mechanism. There are just two caveats. They only serve those who can pay; the rest they ignore. And they only value what's priced; the rest, they tend to exploit.

Those are pretty big caveats.

To your question, what do we do? Do we try to make sure that everyone can pay and everything is priced? The “everyone can pay” story—does that go on to universal basic income and redistribution and ensuring everybody has access, as if everything should be sold through the market, and then we all express our values through the market? I think there are huge limits to that. But let's go to the question you're asking. If we really want to make sure that business doesn't exploit the living world, should we put a price on everything? And indeed, governments exploit the living world through subsidizing fossil fuel companies, or even allowing them to continue to practice.

There are two big projects I'd say are going on at the moment. One follows this logic that says, “What's priced gets protected. We value what we measure. The language of power is money. Treasuries work in dollars and pounds. So we need to bring nature onto our balance sheets. And we need to express the value of natural capital along with financial and manufactured capital and human capital. We need to reflect the value of ecosystem services, like the value of bee pollination, so that governments ban chemicals that kill bees.” That's one project.

I often say to people, “Tell me how you talk about the environment, and I'll tell you what your job is.” And if people say, “I talk about the value of ecosystem services, the value of natural capital, and how we need to bring it into our accounting.” Your job is probably that you’re facing policymakers today, and you're trying to get that wood protected, that bee protected, that toxic chemical banned, you’re trying to make change now, you're speaking the language of power to power for short-term security of the living world.

I totally know why you're doing that. I understand why you're doing that. But there's also a whole other project that's emerging. The people who work in that project will speak not of natural capital ecosystem service value, they will speak of the living world. They will talk about planetary boundaries. They'll come and talk, as the Earth system scientists do, in parts per million of carbon dioxide and tons of nitrogen. Instead of flattening all the information into dollar value, they're actually speaking in nature's metrics.

This is the century of Big Data and it's also the century of natural data. We can measure the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere, day to day. We can see Earth breathing. We can see Earth breathe in and out, through the months and the seasons. We can measure the toxicity of chemicals in the soil or the intensity of nitrates in the oceans. We've got data that no generation before has had, so it would be really weird, in my mind, to say let’s take this incredibly rich data and flatten it in something that was called GDP, invented in the 1930s. And it has one number that's insensitive to complexity or tipping points or horizons. Why would you do that?

My energy goes into this second project where, rather than trying to monetize everything until we’ve got this complete account and we've turned nature into an asset on our balance sheet, let’s just take a whole other verbal framing, and say, actually, “We are part of the web of life.” It's way more complex than we understand. We’re only beginning to understand that. But we can begin to measure and understand the natural world and her cycles and her tipping points and her interdependencies in nature's own metrics. I would rather listen more to the ecologists in the broadest sense of Earth system science, and believe that we're at the beginning of a big project to allow us to speak in her own metrics—and that we understand it. We can combine that with social metrics. Understanding human wellbeing not through income per capita, but through people's access to education and wellbeing and social connection and their resilience and their sense of belonging. I'm all for that project.

Going back to your point about Milton Friedman, the beauty, of course, of the dollar value is it seems like we can measure everything and add it up. This pile is bigger than that pile, so we do this one. And of course that's where all the danger lies, because it reduces the complexity that we knew was there. It financializes nature. If you put a dollar value on something—economists often say, “No, it's not a price, it's a value.” But where we see a value, we smell a price. And when we smell a price, we spy a market. And where we spy a market—go and go and go and the living world just got sold. So I would keep it well away from that financial value and keep it in the language of its own terms. Which is more complex, and we're only just beginning to visualize it and know how to tell that story and see those interconnections. I'm in it for the long project, which I believe is the 21st Century project, rather than the 2021 project of putting money value on nature.

YANCEY: There's a cost of measurement. We don't see it as clearly now, because digital measurement is so much easier, but money was maybe something always worth counting. Counting nature manually in the past might not have made as much sense. But with digital sensors we have the ability to assign or identify value to the most microscopic action or decision or part of our world. To me, it feels like especially this next decade, and I think the coming decades, are about this shift. Today everything moves through this financial conversion—which has crazy high conversion fees like an ATM in an airport or something—and instead we’re moving towards trying to actually represent what's happening.

KATE: So you agree that makes more sense to you? To go more with the natural metric?

YANCEY: Yes. The core project of humanity to me right now is about defining the set of measurements that will allow us to create the world that we want to live in. The notion that finance can be the shorthand is clearly flawed. The argument that this is the best we can do with what we know is fairly persuasive in the past, but I don't think that's true anymore. What we know and what we're capable of knowing is so much larger and the limits of our system are so obvious.

It requires courage, it requires generational change, it requires a willingness to look at the world anew, but I don't know how we can't look at the last five years especially and say that isn't exactly what's happening. To me, it is about data. It's about us becoming more comfortable with different kinds of data. A lot of the pushback against social data—our skepticism has been warranted, but also somewhat problematic. Because we're going to need these measurements. We're going to need to measure ourselves in ways that might feel awkward or immoral or amoral, but I think ultimately are this transition, this adolescence we're going through, to better understand ourselves.

KATE: I like the idea that we're in a data adolescence. We're dating like teenagers, right? [laughs]

YANCEY: Recently I talked with the journalist David Wallace-Wells, who did The Uninhabitable Earth and the venture capitalist Albert Wenger, who's big in climate change. Both of them talked about this new thing they’re noticing, what David Wallace-Wells called “climate self-interest,” where governments and businesses now see decarbonization as in their self-interest. They can see that it will improve public health, but just as much, they can see it will be profitable. I'm curious how you feel about the financial motive coming into solutions to climate change.

KATE: There are certainly companies and sectors that are increasingly, as you say, seeing it as profitable, because, for example, the cost of renewable energy has just come flying down this cost curve. The point that riles me on that is I sometimes hear people from the world of finance or the private sector speaking in conferences as if to say, “Don't worry, we're here now. We'll take this over now. We’re here and we're going to solve it now.” I want to say: “Do you know how many decades’ worth of social activists, of entrepreneurs, of people who do it in their sheds and their garages because they're determined to figure out how to make a solar panel, of people who did it just for the sheer determination of it, who brought this thing down the cost curve for you? Until it landed at a point where you're like, ‘Ooh! That fits in my wallet. I'll just run with this from here now.’” That neglect of all the work that's been done to bring it to this price point for you.

I'm going to reflect on a circular economy, which is very related. We think about decarbonization in relation to the shift to climate change. But the circular economy, where we use resources again and again, is crucial to reducing the material extraction of industry. That’s one crucial part of protecting biodiversity. I've seen in the space of circular economy promotion, people—again, wanting to make it appealing to power—talk about circular advantage and make the self-interest argument. “It’s in your interest to have a circular supply chain, because, actually, you can mine your own materials, you can control them, it'll become cheaper in the long run.”

And of course, often, if you want to speak to power, speak to companies about profit and their own self-interest, and it is going to first turn a head if that company is still typically owned and financed in a way that what it’s driven to do is deliver big profit. But the danger is that they will therefore only listen to the need for circularity to the extent that it delivers on profit. It's like saying, “Here are some strategies that deliver circularity.” And if you're coming at it from the self-interest perspective, what you do is you just listen to them and you pick off the ones that also increase your profits, rather than saying, “What kind of business is compatible with life on this planet, given all that we now know in the 21st century, and what transformations need to happen?” And by the way, that kind of business is one that's going from being a degenerative to a regenerative business, and also going from driving divisive returns to more distributive returns with everybody who co-creates the value that business creates. Those are the dynamics of businesses that are compatible with bringing humanity into the Doughnut.

So we need your business to transform: in the materials it uses, in the technologies it uses, and in the design, the purpose, the governance, the ownership, the finance of your enterprise, so that you can become regenerative by design. So it's not enough for you to turn back to me and say, “Oh, yeah, yeah, we're doing circular, but we're doing these three bits because they were really great for our bottom line.” That's you capturing the notion of circularity and driving it to your old purpose, which is driving returns, rather than taking on the living purpose and saying, “We need to be part of a regenerative planet. And wow, we as a business need to do some deep transformation. And we need to figure out how we can transform ourselves so that we become circular by design, because that is what the 21st century demands.”

So there's real danger of opening the door with the self-interest argument. The trouble is that the only part of the body that comes through the door is the self-interest. And it just sticks around for what works for it and only takes that up, and doesn't transform its wider purpose.

YANCEY: So to use your language from earlier, maybe the financial motive is a 2021 solution, but not a 21st Century solution.

KATE: Yes. Exactly. And again, tell me how you talk to business and I'll tell you what your job is. Iif you tell business, "What's the financial interest in decarbonizing? What’s the financial interest in circular advantage?” You’re somebody who's really trying to get those big powerful companies today to transform, because we know they want to transform towards COP26. And in this decade you want short-term, and the danger is we win this particular battle but we lose the war, as it were. It’s not a great metaphor, is it? We keep framing things in an old frame that works for now, but we give up the chance of transforming to the mindset we definitely know we need for the longer journey.

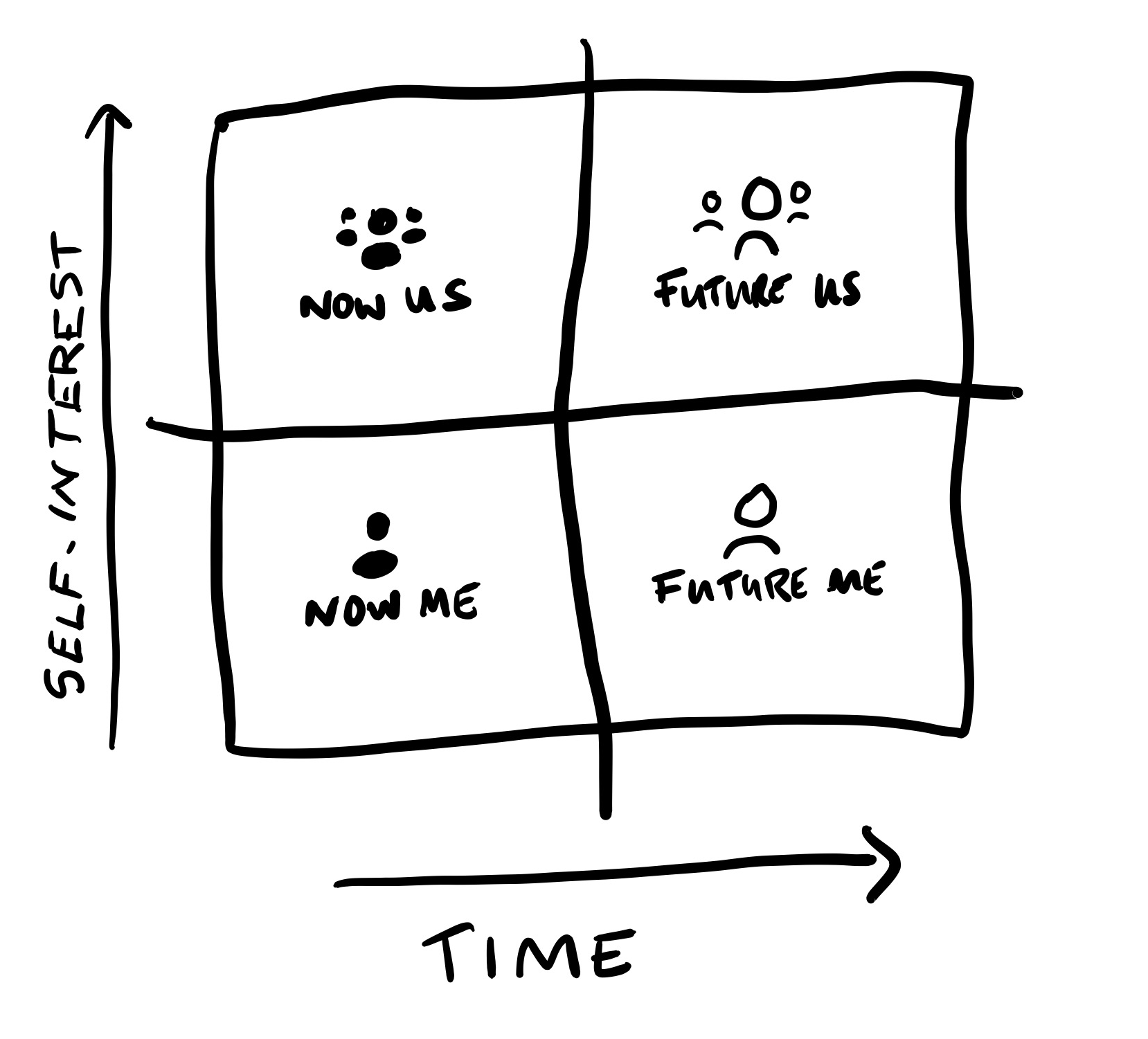

YANCEY: Absolutely. So my project is called the Bento Society. Like you, I am a food-themed metaphor. In my case, the bento box. My project is around the question of self-interest. I thought a lot about this question of self-interest after working on Kickstarter, and like you, I had a visual doodling moment one day of drawing a hockey stick graph, thinking, “This is like the crucifix of self-interest today. This is our emblem of ‘whatever I want’ growing so fast, the line slopes up.” Then I had this light bulb moment seeing how the x-axis of that chart extends from now far into the future, and the y-axis of self-interest also extends: from me to us. As our self-interest grows, so do our responsibilities.

Suddenly my hockey stick graph was these four quadrants. I described them as “Now Me,” what I as an individual want right now; “Future Me,” what the older, wiser version of me wants me to do—that person becomes real or not real based on the choices I make each moment. In the top left, there's “Now Us,” the people in my life who count on me and vice versa; and the top right is “Future Us,” my children and my future self. When I drew this, I thought all of these spaces are in my self-interest. It's not just this short-term individualistic space. Next to this picture, I wrote a simple description: “beyond near-term orientation.” That's what this little 2x2 graph did. I realized that made an acronym for Bento. Like you, I'm running with that metaphor. Many parts of your story I connect with.

The core idea is that people are driven by self-interest. However, in the West we've defined ourselves by an incredibly limited version of self-interest, of short-term individualism. I think if we can shift how we think of our own self-interest to incorporate a future self and the people that we love and care about in our lives in just a slightly better way, there’s a number of really big things that unlock from there. I'm curious how you think about self-interest, how you define it, and where that fits into the Doughnut world.

KATE: So, two things. First one: I like your bento box. I will never eat out of a bento box again without thinking, “Rice is in Future Me.” [laughs] I also, of course, like the playful foodiness of it. And I think there's something very powerful about making ideas playfully light, because they're not intimidating, right? A lot of people are intimidated by economics. But anybody who hears Doughnut Economics already knows this is not an intimidating space. Come on in.

So self-interest. What that triggers in me: immediately I think of Adam Smith. The classic phrase from his 1776 book said, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, and the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interests.” So it was self-interest at the heart of that market mechanism. They make the bread and the beer and the bacon because we're paying for it. That's why there's supply day after day after day. That goes back to this brilliance of the market mechanism.

The idea of self-interest sits, again, at the heart of the rational economic man, the character put at the center of economics. It was John Stuart Mill who did something really unhelpful around this. He was trying to define political economy and distinguish between the political economy and philosophy and social science. To do that, he said, “In a space of political economy, we don't take the whole of man in society, we see him as a being who desires to possess wealth.” Now he doesn't use the word self-interest there, but it's a very narrow—“I,” so a being, the individual. And he has this desire, and it's to possess something. So there's a very strong articulation of self-interest there. And by doing that, John Stuart Mill said, this is the characterization of humanity we're going to put the heart of economics. Everybody over the centuries added all these other [characteristics], like, “And he has perfect information, he can see in the future and the past, he knows everything and he's independent, he's not influenced by other people's opinions.” What an absurd character. We know that we're deeply social, we’re the most social of all mammals.

So I am not drawn by the idea of self-interest. It's really interesting listening to you say it. I would rather say “interest.” I have interests. Because the word “self,” it pulls us back to the “I.” Now I suppose you could redefine self-interest in a very broad sense. But I like the idea of, “Of course, we have interests. Now, what’s the breadth of those interests? Who is included in those interests? And how? And of course they're related to us, and how far forward and back do we go in those interests?”

My partner is the philosopher and writer Roman Krznaric, and he's written a book called The Good Ancestor. We've talked a lot about this, thinking about future generations. One of the activities he invites people to do is to imagine their child when their child is 90 years old at their birthday party. They’re standing up, wobbly, at their chair, and about to give a speech about being 90 years old, and they glance over and see a photograph of you. They're gonna say something about you, and what do they say about you? This brings in the idea of the legacy that you've created for this person, the future. But when we were talking together about this visualization, this idea, what really struck Roman very vividly was, “If I really care about my daughter”—so my daughter, so you could say that’s Future Me, right? The first extension away from me is my child. “Future Me” through my child. “If I really care about my child in the future, I have to care about the society of which she’s a part, because there's no way she can survive alone. If I care about my children, it drives me to care about the community of which they're a part.” And so I find that a very intuitive and a beautiful expansion—so I'm going with your sense of the self, actually, so myself living on in some sense through my child. But then if I care about my child, well, I have to care about the community.

What it really does is take us back to what we know, which is we're such social animals. We are deeply interdependent upon one another. So if I care about myself, I have to therefore care about my community. Because I know it's what sustains me. In the very same way that if we care about humanity, we have to care about the planetary boundaries in which we live because we're part of that web as well. It's not humans against nature, it's humans sustained by and therefore dependent upon nature. It's not my interest against the society, I’m dependent upon society, so I have to care about its wellbeing.

But I want to ask you back: how do you think about extending from self-interest out to say, Future Us?

YANCEY: The Bento as a scaffolding makes it very present to me. It's something I think about all the time. I use the form every week to make my weekly to-do list. Every week I have my Now Me to-do’s, which are work and errands, go to the bank. My Now Us to-do is the people in my life I need to be in touch with this week, who I need to give energy to. My Future Me I think of as my Obi-Wan Kenobi voice that tells me, “Be patient, don’t be so thirsty, just relax.” And Future Us invites me to think about the world my child will live in. Each week I ask myself, “What can I do in the next seven days that positively contributes to them?” Inevitably it comes down to me trying to learn something, me trying to teach something, or me giving my time in some way.

Because of this, Future Us is a part of my now. It is very actively a part of my thinking. I think of these things as being in my self-interest, but not in a way that’s selfish. It’s, “I care. I'm a part of this, I am larger than this entity sitting in this chair at this moment.” All of these spaces are true, and I'm trying to be opinionated about them. I'm trying to learn how to operate within them. There's a feeling of coherence, of wholeness. I’ve learned that a good day for me is a day when I do something that satisfies each of these boxes. I can feel the difference of how it fills me up.

I've been living according to my Bento for three years. In front of me, I have my values written down. There's a Bento for the Bento Society, and there’s thousands of people who have done this at this point. It's trying to articulate those spaces and make them a part of your life, rather than these hazy visions that you feel guilty that you're not thinking enough about.

KATE: Two things. One way I could think of coming to reconcile myself with this use of the word “self”—when I just heard you, I can express that at as, “These are the interests held by myself.” I have a self, and this is the whole range of interests that I hold, these are my self-interests. So it's not that these interests are in service to me, but these are the interests that belong to me, and are held by me. I can work with it; it feels good to me that way around.

And also, you were saying there are things I can do for Future Us, and of course some of those things might feel in tension. Some midlife crisis person says, “Now Me, I want to buy a red Ferrari.” But then looks to Future Us and says, “Actually, not only should I not buy a red Ferrari, I should actually get rid of my car because I live in a city and I don’t need it.” So it's about letting go of things as well, right? So I can bring into the Now Me—I can transform what I thought I wanted because of my reflections from the Future Us.

YANCEY: Yes. I think a lot of our anxiety we feel on a momentary level is that lack of clarity about the larger context we're in. When I first had the idea, I had to do a number of things to make sure I wasn't crazy. A week later I asked a friend of mine to arrange a salon. I was like, “I want to figure out if I can say an idea out loud to strangers without throwing up, please. Can I come to your house?” So she invited people and I shared the idea to thirty strangers. Learning how it connects with people.

So I have one last question.

KATE: Before you go there, I want to riff with the Doughnut and the Bento. So, we could of course put the Doughnut—well, it certainly belongs in Future Us. Right? Because it's a big vision. But it's not necessarily future. Well, I don't know if it fits inside the Bento, how it relates to the Bento box. You could have mini Doughnuts in there somewhere. But then not everybody would value those things. Or do you believe that by holding that space of the Future Us, if people really reflect on what we need, and what we'll need in the future, it helps bring around a more community-oriented and an ecologically-aware mindset? Have you seen reflected in people that it helps?

YANCEY: One of my beliefs is that people's values are justly earned. How people see the world is based on their experience and we have to respect that and listen to it and not to try to change it. To me a value system that asks someone to adopt a different set of values is a nonstarter. But if there could be a system that puts your values in a larger context and empowers you to reflect on them—to me, that seems wholly positive. What it does is invite you to develop an awareness. It invites you to develop an opinion. It says, “You don't know what's important about your relationships? Really? Well, let's take a few minutes to think about that.” It prompts questions. I have a very strong feeling that imposing values on one another is a losing proposition. I do trust in the goodness of people. I don't think everyone's good, but I trust in the goodness of people.

I saw Greta Thunberg on cable news this week and the TV announcer asked a very 20th-Century question. He said, “If you had total power to do whatever you wanted, what would you do?” And her answer was, “I would never take total power. There would be a democracy and it would be what the people wanted to do.”

I have that kind of trust in people. That's where I connect with the Adam Smith idea of trusting someone to live according to their self-interest. Maybe what Adam Smith was wrong about was the baker wasn't motivated by money, maybe the baker was motivated by a desire to be a great baker. “I will make you bread because it is in my Future Me self-interest to be a great baker, because it's my passion.” That is still his self-interest. That to me is just as true as any other plausible explanation. It speaks to this multiplicity of values and the dimensionality of self interest. That speaks to our humanness and allows us to be bigger than who we are as individuals.

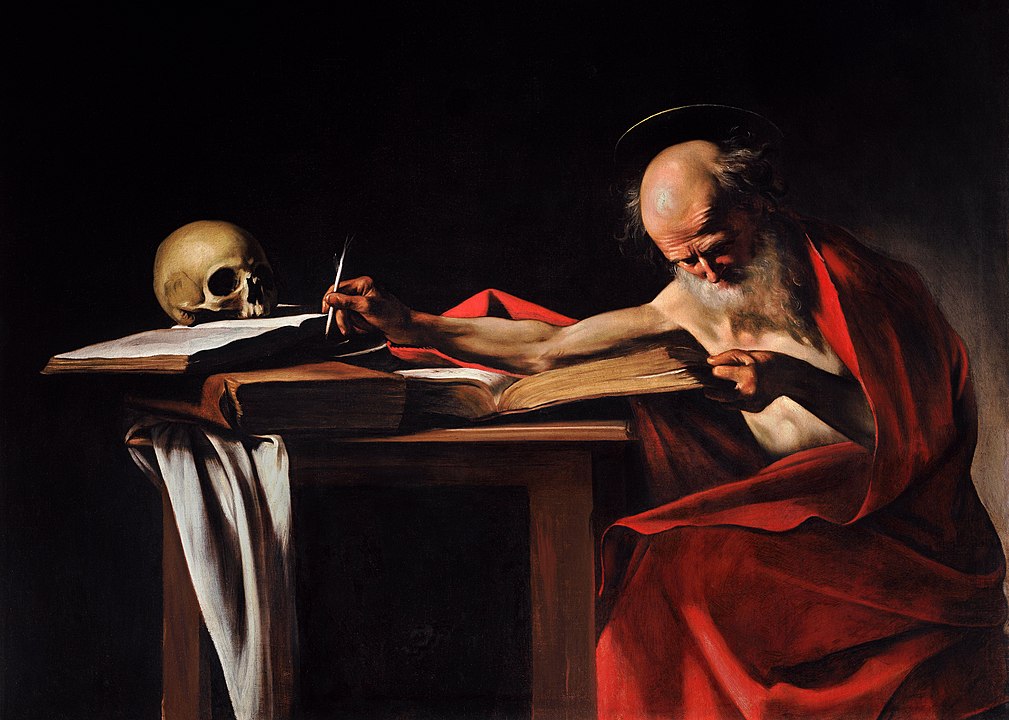

When I was facing my “what the hell am I doing in my life with this crazy idea, I'm gonna die a failure with my ridiculous idiosyncratic concept” dilemma, I went to an art museum. There was a Caravaggio painting called Saint Jerome Writing. It has a monk hunched over a big, thick book. He was very old. And on the other side of the book was a skull looking back at him.

I looked at that picture that day and thought, “That skull was the last person sitting in that chair. Sitting out of frame is a long line of men and women monks waiting their turn to write maybe a paragraph in this book. And that’s life. That is life in a best-case scenario. You're adding on to something someone else did, and someone else adds on to what you did.” The notion that I should only think about myself in terms of this time while I’m alive, I could feel the absurdity of that. Seeing that painting and thinking about this idea, I felt a liberation. I thought, “What I'm doing is not about me, it's about something bigger. I'm just this vessel, and I'm very happy to be a vessel. I feel lucky to be a vessel. What a great task to be given by the universe.” But it's scary. It starts with accepting a different notion of self.

KATE: That totally resonates with me, and with what I told before about drawing this doughnut and then realizing it had been in my own mind. And André Gide: “Everything that needs to be said has been said”—let’s say it once more with doughnuts, let’s say it again with bento boxes, and let's keep bringing these ideas back. And they will need to be brought again and again in different ways and pictures and sounds and languages. And to be a vessel in that long chain.

I love saying the Doughnut is never the end point. Goodness me, what will it become? What will somebody else pick it up with and flip it over and create it into something new? I really share that. I think it's a really healthy humility to hold.

Whenever we share the Doughnut, our first principle is we never ask anybody to talk about it, use it, promote it. Because as you said, why would you push values on somebody who doesn't want those values? So everybody who's ever used the Doughnut, it’s because they've seen it and thought, “This really resonates with something I was already feeling. And I'm going to use it to put into practice something I wanted to do.” That means it's having this spontaneous uptake around the world of little community groups that are popping up everywhere, or city governments that are saying “we want to do it,” because they're finding it useful to them. There’s nothing that could give me a greater thrill [than] seeing this part of our experiment working in this way. Also knowing that in twenty years’ time we won't be talking about Doughnuts. I hope they won't be, because the Doughnut is a way that helps bring it into our thinking, to the point that I hope that regenerative and distributive design—because these are the dynamics we need—become so central, so familiar to our thinking, that we don't need the playful frame of the Doughnut to bring it into the room anymore. It's just there. And so that word has gone and it’s, “Do you remember in the early 2020s people were talking about doughnuts? Isn’t that bizarre?” So let the Doughnut be one of the skulls on the table that we've moved past, something else came along, and we progressed.

YANCEY: Amen. So my very last question. And this has just been so wonderful. My heart is filled with so much joy being with you today. The subtitle of Doughnut Economics is “Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.” So what's distinguishing about the 21st Century versus 20th, for economics or other fields? What is this era that we're in?

KATE: Instant answer? First of all, I think we're in what people call the Anthropocene. We realized that humanity has become the major driver of change at the Earth system scale. It turns out the sky is not so big, and the oceans are not so deep. We have gone—from Herman Daly's frame—from empty world to full world. So if anything I have to say, “Here we are, we’re in full world.” Let’s call full world 21st Century, and it's begun with multiple crises. It began with financial meltdown, it began with climate and ecological breakdown, now we're in COVID lockdown, and these crises are sending messages to us again and again and again that progress does not lie in endless expansion. It lies in balance.

I'll also say that, if you look at the economists of the 20th Century and back, they may have a variety of views, from John Maynard Keynes to Milton Friedman to Adam Smith to Karl Marx, but they've all got one or two things very much in common: they were all men. They were all white. They were all from the global north. They were from colonizing countries. These traits of these economists delimited what they did or didn’t see, and what they did or didn't think was important. Adam Smith, writing about the power of the market and interest, he didn't notice that it wasn't just the butcher, the brewer, and the baker who put his dinner on the table, it was his mom in the unpaid caring work of the household economy. If he had noticed, he could have invented feminist economics back in the 1770s. He didn't. So it took 200 years for women to say, “Hello, you've missed out the unpaid caring economy.” David Ricardo thought that land was actually the scarce factor and he was putting it at the heart of his theories, that we're going to run out of land, and then, “Hey, presto! We found land overseas. Other places we can take over. So actually, let's change our focus. It's going to be labor that we're going to run out of.” And this is the reason why we still focus on labor productivity. Why are we obsessed with labor productivity? There’s mass unemployment, why are we trying to chase more and more productivity out of each person?

Who we are shapes what we pay attention to, shapes what we do and don't see, shapes what we put at the heart of our theories. Another part of the 21st-Century economist is the diversity. That's essential. Bringing women, people of color, people from different class, people from the global south—whose starting point is different. Amartya Sen, son of Bengal, did not start his economic thinking with, “Hello, here's the market supply and demand.” He starts with, “Why are some people facing famine, and have no entitlement and access to the market?” Ha-Joon Chang, born in South Korea when people called it a third-world country, watches his nation rocket up in economic success by following trade and investment rules and industry rules that are completely counter to what the World Bank was saying you should do: “Liberalize everything.” Women, from feminist economists—and of course, it's not just women saying “we see the unpaid household economy,” it’s also women saying, “Hang on a minute. Don't be so down on the state. Actually, the state is a great entrepreneur.” Mariana Mazzucato, Stephanie Kelton.

This brings us right back to why we took that little triptych photo. That's one of the diversities that's come into economics, from more female economists. But more people of color, more people from a working class background need to say, “Actually, here's a class-based analysis, Marx was right, it's essential. Are we labor or are we capital?” It matters, and it hasn't gone away. Let's bring it back in. So to me, 21st-Century economics is also about that diversity of perspectives.

And the last thing I'll say is I think it's fantastic that worldwide there's a student movement. In some countries, it's rethinking economics. It's plural economics. What they're calling for is a pluralism in economics teaching. There's no one school of thought that has it right, so teach us that plurality. And while we do it, can we decolonize economic thinking and bring in that plurality as well, so that we can be critical thinkers and recognize the diversity of views and understandings that it takes to be able to see the whole? Because no one of us can see it all. We need the multiplicity of our views to have a chance at seeing the complexity of what's before us.

YANCEY: Wonderful Kate. This has been amazing. And we didn't even get to talk about all the great things the Action Lab is doing, which I'm also very interested in. Another time.

KATE: I’m thankful to you! It was when the Bento met the Doughnut and when the Doughnut met the Bento, I really enjoyed it.

Linknotes: