Interviewee: Hank Willis Thomas

Background: Artist exhibited at the Guggenheim, MoMA, Whitney

Topic: Playing infinite games

Listen: On the web, Apple, Spotify, RSS

“A lot of people that I have come to admire are infinite game players stuck in a finite game… Playing outside of the rules of the game, and making up our own rules, but somehow still abiding by the boundaries of the finite game that our society has created for us.” — Hank Willis Thomas

Sup y’all, and welcome to the Ideaspace.

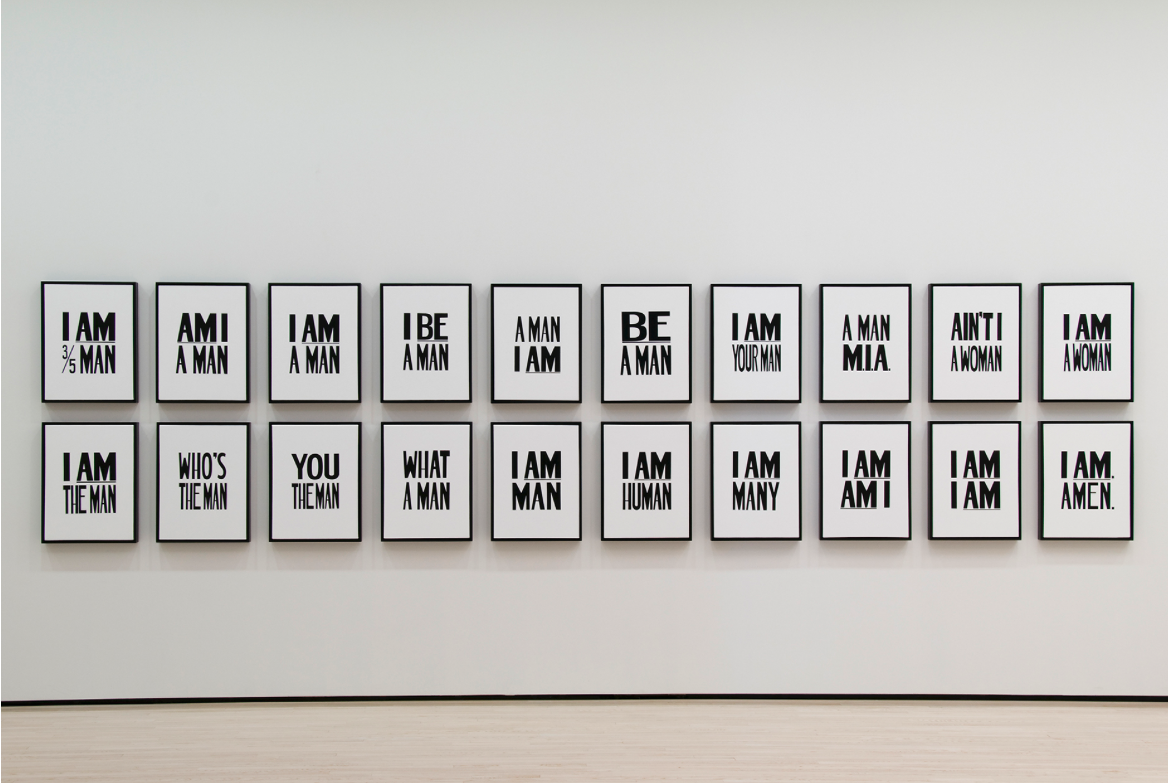

Hank Willis Thomas is a conceptual artist working primarily with themes related to perspective, identity, commodity, media, and popular culture. His work is challenging, funny, and alive in deep and visceral ways.

Hank is a frequent public artist with major pieces in cities and parks globally, work in the Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim, and Whitney, and many solo shows at major institutions around the world.

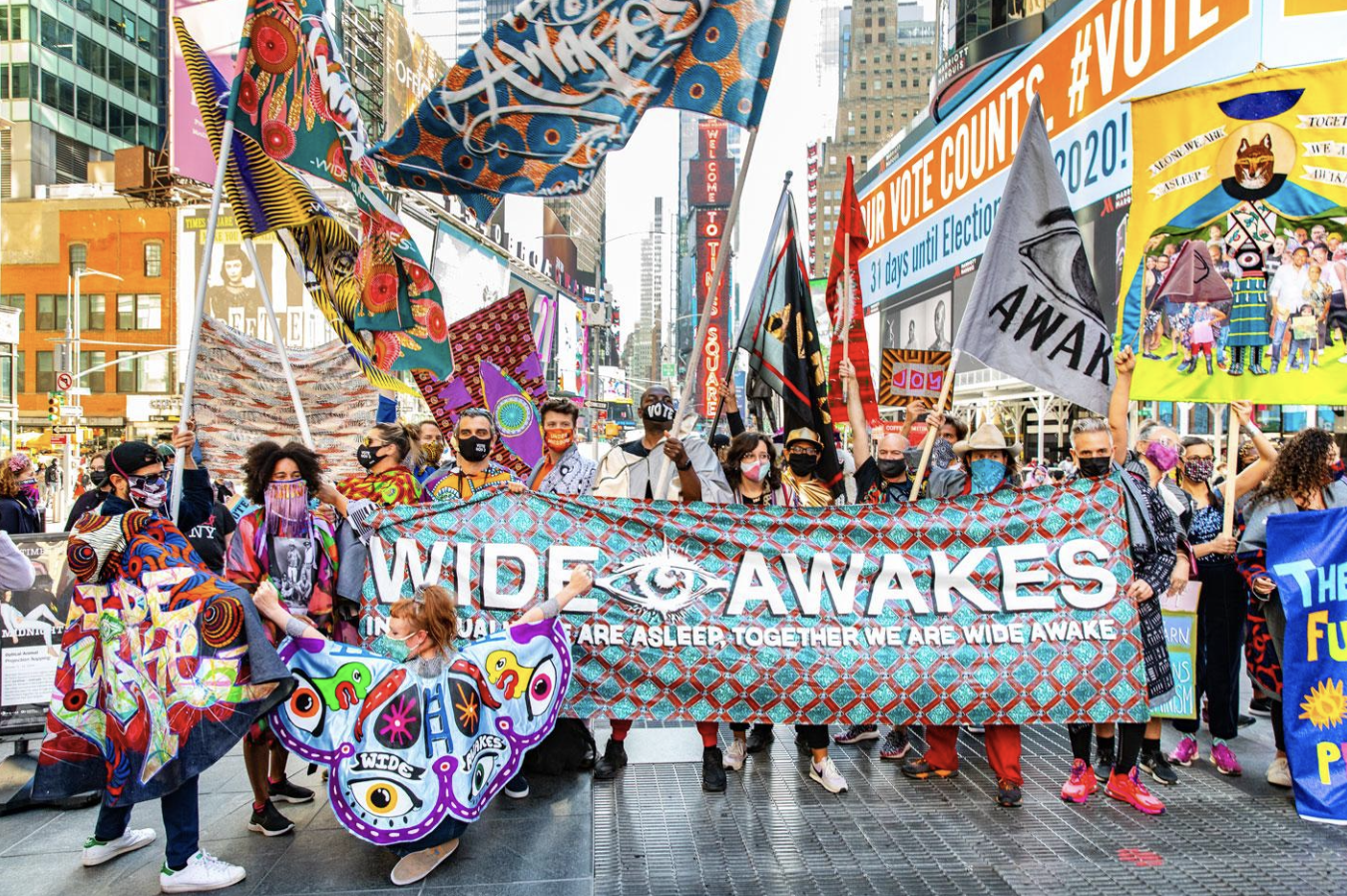

In addition to his work as an individual artist, Hank operates in many other contexts, including creative activism: from putting up billboards in all fifty states to reviving an Abraham Lincoln-era political movement for the 2020 election.

I admire Hank as someone who truly embodies the Bento. He operates in multiple dimensions at once, pairing a phenomenal personal practice with work that widens the lens, involves and invites public collaboration, and speaks to a larger “us.”

In one of my favorite Ideaspace conversations so far, Hank and I had a reflective, sensitive, and strikingly honest discussion of his work, the impossibility of defining Black male identity, and how to operate as an infinite player inside a finite game. Listen to our full conversation, which includes the live performance of a Bento exercise that we went through together, on the web, Apple, or Spotify. A full transcript is below.

YANCEY: We know each other socially. Not super well. But we have a lot of life connections. I wanted to talk to you because I think of you as someone who really—to use my language—embodies the Bento. You’ve got a great individual practice, amazing work; I've spent the past month really living in your work and I’m so moved. But you always widen the lens: look beyond the West, look beyond your culture, see the language. You're always adjusting that lens. And you’re also always speaking to this larger “us,” whether it's as a Black American, whether it's the political work you're doing now. There's just a lot of dimensions in which you operate. That’s what made me curious to talk to you, to think about what you're thinking about. So my first question is: what's on your mind right now? What's what's going on today?

HANK: What’s on my mind: I hear sirens. And it reminds me of this time last year, where in New York City there were sirens blaring 24/7 basically, because of the overwhelming nature of the coronavirus pandemic first having impact on our healthcare system. That's something I’m thinking about right now.

YANCEY: We were talking right before the call started about our ages. You are 45, I’m 42. And I've been thinking about my age a bit lately, because I'm seeing people that I think of as peers in real positions of power or influence. It strikes me that our age group is coming into its own—maybe an early peak of our lives or something. I wonder where you think about yourself being in terms of life.

HANK: I am definitely in a moment and a phase of re-definition, re-examination, which I think is not uncommon during this pandemic, and also for someone who is entering middle age. I'm looking at things like your book, and the ways in which some people have built philosophies and principles around their lives that almost function as a rulebook, that are a pathway for the future, and wondering if it's time for me to begin to talk about an ethos of my work in practice. Not so much for others as much as it is for myself. There's also a connection, an element or a necessity for intellectual, spiritual, and emotional growth that comes with this transition into a new phase of life where I have a daughter, I am in my mid-40s, and not able to zip around the world and do whatever I want without there being real consequences. So in a way it's a new lease on life.

YANCEY: I've been thinking about it like it's the start of a new part of life. You mentioned a rulebook or a guidebook, playbook. Have you been guided by something up to this point? What's gotten you to this point where you are right now as an artist? I imagine if a seventeen-year-old you saw where you are today they’d probably feel pretty happy. But I wonder what has guided you?

HANK: If seventeen-year-old me saw me now he would wonder why I wasn't happier. You asked the question of how I got here: if we can have a level of success and validation and opportunity and comfort through your work, through your friendships, through life choices, and still not be at optimum happiness, I think that's where I start to really wonder, “What have I been doing?” I'm not unhappy. But am I living in my essence? I'm not sure. That does fall into this chasing external validation and external references or objects that suppose or present a security. That pursuit is an endless pursuit because when you don't have the internal security and the internal comfort and the internal validation, how could it be fulfilled outside? It's not something I was consciously doing, but when I hear your question: what would seventeen-year-old me say? He'd be like, “Dude! You just did that!”

YANCEY: Forty-five-year-old Hank could give a lot of perspective to seventeen-year-old Hank and vice versa too.

HANK: I'll just say it's not gonna get much better than this. Maybe not that much worse, but just enjoy it, don't be so stressed out.

YANCEY: When you say things like that to yourself, do you listen? Does that work?

HANK: Whatever I say to myself works. That's why I want to be conscious of what I say to myself. I’ve come to realize that the story I tell myself about any moment in my life becomes the dominant narrative. I would love to master the art of telling the best story I can tell for my own and collective advancement.

YANCEY: I saw in some of the stuff with the Wide Awake project you reference James Carse’s work Finite and Infinite Games. How does reading that connect with externally validating goals and how you think about your life?

HANK: I came across the book Finite and Infinite Games and a vision of life as play and possibility that was written in 1986 by James Carse, who was a theologian and, I guess at that point, a somewhat novice game theorist, perhaps. He was a person who had spent — he passed away just last year — most of his life in search of if not meaning, in search of excellence in life. That is very much about the game of life. In the book he talks about there being two kinds of games: finite games, which are games that come to an end when someone has won, and infinite games, which have the object of the game being continuing to stay in a state of play. So I would hybridize that to say that finite games are for winners and losers, and infinite games are for the players. I recognize that in me, and I think I projected this onto you. A lot of people that I have come to admire are infinite game players stuck in a finite game. We are always playing outside of the rules of the game, and making up our own rules, and actually in an active process of play, but are somehow still abiding by the boundaries of the finite game that our society has created for us. When I recognize that I'm really playing this game to just stay in the state of play, it doesn’t matter how old I am, it doesn't matter who I'm with, it doesn't matter how much I have or how much I don't have, or where I am, as long as I am actually in creativity and in movement with my thoughts and my energy. That was the beginning of an awakening for me about embracing my power.

YANCEY: Do you work in a structured way? Has that evolved a lot over time?

HANK: I work in a structured chaos. At least with my life, there are patterns and there are methodologies that really come up from just riding the wave and watching the same opportunities and same obstacles come up in different forms. Then navigating through them. It doesn’t seem like it's a structure, but I think I've created these groups where like, “Oh, I created that problem. I created that success.” There is a method to the madness that even people who have worked with me for a long time see after a while.

YANCEY: When your work goes in another direction for a project, like say you're doing textiles and you want to learn about something new, how do you dive into something you haven't done before? Do you talk to people? Do you have the kind of brain that figures it out? How do you think about things like that?

HANK: I like to know where things can go wrong. I am very big on not learning too much about how it's done, just learning how not to break it. Whenever I think about something new, I’m like, this is interesting. I see that it's been done this way for a long time. What happens if you do this thing that hasn't been done or you’re not supposed to do? Does that ruin the whole thing or does that just open a new door? That's where I think I spend most of my energy as a creative: tinkering and retooling ideas and practices and techniques that had been well-weathered, but not with such a rough and playful hand.

YANCEY: When we were setting up this conversation, I got a text from you saying something like you’d get back to me in a week or two because you only check your email that often. Which just made me wonder: what is your online life like? How do you relate to the internet?

HANK: I tend to say yes to things. I don't know how not to. So I just delay my yeses by not opening up my inbox and saying yes to everything at once. And then I don't say anything for a couple of weeks, and then say yes to a bunch of things. I have a great relationship with the internet. I am also trying to have a great relationship with myself. I don't believe you can do both at the same time. Me and the internet are not dating, we're actually in a very committed, loving relationship — which myself has issues with, and maybe gets a little jealous.

YANCEY: You have collaborated on a lot of things. What is your collaborative energy?

HANK: My studio practice is also pretty collaborative. It's just that I get more of the credit and more of the creative criticism. In a lot of ways I'm more invested in my publicly built collaborative projects because it requires more. It requires me to earn and maintain the trust of other people and to make something real that has the hands of a committee on them. To hold it is a pretty strenuous journey. That's what I love about the Bento, which I haven't fully mastered, but the conversation around it is really how if we could start with this idea, everyone being really transparent of the Now Me and the Future Me and the Now Us and the Future Us, how would we actually then collaborate? That's why I think This Could Be Our Future is a really beautiful metaphor for everything that I believe in. It's not about me, it's about us. And I want to be there, and not alone. Right?

YANCEY: Absolutely. The Wide Awakes was first a Lincoln-era political movement of young revolutionary progressives, “the world can be better” people. You and a bunch of great people brought the idea back in 2020 and did voter drives and other activism around this myth of the Wide Awakes, making it present again. On a banner in one of the marches, there was a line that said, “Individually, we are asleep; together, we are wide awake.” What does that line mean to you?

HANK: One of the many people involved in this, Tony Patrick, is the one who said that. What he said is slightly different, but someone else must have heard it. Every moment that I have with another person is a shared moment. You and I are making reality together, and someone, I hope, is hearing us make reality together. We often don't wake up to our aliveness unless and until we are interacting with another person. When we both approach that with the awareness, with the gratitude and respect that it deserves, that's the magic of life. You and I have experienced it, but when you get to that point with another person where we're like, “We're alive and we're vibing, we’re together, we're awake.” I'm not thinking about the sleepwalking element of like, “I have to go do this;” the things that feel obligatory rather than generative. That's my interpretation of it. But what I love about the Wide Awakes as it's grown — and I've been sitting back a little bit to see — there are a lot of people, a lot of whom I don't know, that are doing this, and we're wondering about what it means to not have boundaries in a collective. The collective is also about the boundary, but if the barrier for entry is just seeing that you're part of the collective, how much stronger is it? That what I think it's about. When I see you and you see me, what do we then do together?

YANCEY: For you, what does it feel like to be an artist? Are you always an artist? Is that a jacket you put on sometimes?

HANK: I feel the title artist is a sham. I don't know how to paint or draw, and that's what I thought artists do. I studied photography, but now everyone is a photographer, so I'm just an Average Joe. Or Hank. Just your Average Hank. I always introduce myself as a person, because — and it's inspired by a quote by James Baldwin, which I hope I get correct, where he said, “The artist’s struggle for his integrity must be considered as a metaphor for the struggle which is universal and daily for all human beings to get to become human beings.” What I take is that the artist’s struggle to be their best self in their art form, and the master of that craft, is literally the same as the struggle for each and every one of us to be the best person that we can be. If my artistry is really a metaphor for my personhood, aren’t they the same thing? Because they are both creative-making practices, and it's only as good as the attention and the energy put into it. A lot of the way that we've actually colonized humanity through the marginalization of us, saying, you're an artist, you're a consumer, you're a tech person, limits us from being the whole people we are. Remember, in other societies and other moments of human existence, everyone was an artist. It's not about can you dance, it’s will you or do you. If we can get back into this idea that our daily lives are acts of creativity, imagine how governments can change, imagine how the world can change.

YANCEY: A lot of your work has sports in it, which is atypical for “serious art.” Is that the context of your life—that’s what you're interested in and you see art in everything? Is that something else?

HANK: I’ve never been good at sports. So that's probably part of it. Being a Black American male when I grew up, and not being good at sports, and being named Hank — even though it was Hank Aaron! — was just not a cool thing. I had to spend a lot of excess energy trying to prove my worth outside of machismo. There were others — my cousin Songha, who passed away — who were really good at everything that they did and found it unfulfilling. I remember one time, Songha said what he didn't like about playing sports that he was really good at. He had a promising basketball career and he quit. I asked him why he lost interest, and he was like, “In order for me to be good at my job, I would have to look someone in the eye and make them doubt themselves and do something to make them feel bad about themselves. I just could never do that.” That had a real impact on me about what the finite games competition — “I’m a winner you're a loser” — does to human beings. So there's that.

Then there's also the reality that for many African-Americans, the first glimpse of opportunity in the United States was through sports and entertainment, because it was a playing field, so to speak, that you can prove yourself on. The beauty of these infinite games is that you had these, again, infinite game players in the finite game, but they were playing the infinite game. They changed the style of play, they changed the rules of the game, because they brought a level of passion and creativity to it that was about staying in the state of play. That's where I subconsciously got really attracted to sports, because there is so much that has been done through people like Muhammad Ali and Wilma Rudolph and the Williams sisters, who were first the spectacle, but then became a movement, so to speak. For them to be the descendants of slaves, whose spirits were expected to be crushed centuries ago, who still deep within them have this perseverance, is something that I'm forever inspired and driven by.

YANCEY: You have so many great pieces with outstretched arms, often in a sports context, but also in a police context and a social justice context. What are the arms in your work reaching for?

HANK: It sounds cheesy, but they're reaching for you. Reaching for your attention, but often they're actually just reaching for you. That's what life is about. It's about reaching. For me, about making a connection to things we want, and things we care about, and then being able to hold them. The metaphor of the ball in these things: that is your potential in sports. Your whole potential is dependent on what you do with this ball and your mastery with it. That can be a metaphor for your marriage, for your child, for your health, for your mental health, for your career. That ball, in that moment, what do you do with it? I love playing with that moment where the ball is about to leave your hand and maybe achieve the goal, or it's about to be dropped, or somebody else is trying to take it from you. Those are things that I just love to play with.

YANCEY: Thinking of the piece, I think it's called Promise, which is like Dwight Clark, The Catch, it's one hand catching a football. Going back to earlier, I wonder, at the moment, he's catching the football—does that person think, “Why am I not happier right now?” [laughs] In that moment probably your conscious mind isn't there. But maybe after the game, that person is thinking that.

I really loved Question Bridge, which is Black men asking and answering each other questions. Some of that looked scripted, a lot of it was just interviews. What was the goal of that project, and what did you walk away from that with?

HANK: Wow, well, that actually was not scripted at all. But you wonder—even I, being in the room for most of the conversations, was like, “Did you prepare for that?”

YANCEY: I was thinking scripted in the sense that you had people responding to some of the same questions.

HANK: My collaborator, my friend and former professor Chris Johnson, had done this project in the 90s where he wanted to facilitate a conversation across the class divide in the African-American community in San Diego. He felt that if you had people who saw themselves as different from each other sitting at the same table asking what might be seen as threatening questions, it would quickly devolve into back-and-forth. He thought that it might be more effective if he acted as a ferry, where someone could ask a question of someone that they felt that they were different from or they had an issue with, and he could go to find someone that fit that description, and show them that question, and then get that authentic answer back. This idea of a video-mediated discourse was something that he thought was exciting. He did it in 1996. Around 2006, I found a VHS of it, and was like, “This is pretty interesting to think about.” I never had seen people be as raw in their questions and their answers, but also there being, for lack of better word, a level of civility.

I said to Chris, “I would love to do Question Bridge around Black men.” I wanted to do that because I've been a Black man my whole life, and I can't define Black male identity. And Chris is also a Black male, and has also struggled with the blackmail of race and gender, as society has imposed it on us. And Bayeté Ross Smith, our other collaborator, also a Black male, and Kamal Sinclair, our fourth primary collaborator, is a mixed woman, half-Black, half-white, if you believe in race. We wound up on this journey where we would go to self-identified African-American men and say, “Do you have a question for a Black man that you feel different or estranged from?” Then they would pose a question to the video camera, and then we would take that camera — like someone said, “What’s so cool about selling crack?” We're like, “Uh-oh. That’s not a question you could just go show anybody.” Chris started to teach meditation in San Francisco County Jail to get access to people who could authentically answer that question. We wound up going about a year later into the jail and showing that and other questions like, “Do you really feel free?” and “What makes you better than someone else?” We were shocked by the fact that you could take any question and there would be five, ten different answers. Our idea was to take the best questions and the best answers. In reality, they were just different. That was a metaphor for what we really were thinking about in general, which is that there's as much diversity within any demographic as there is outside of it. When you have five Black men answering the same question in five different ways, you start to say, “Oh, this container doesn't hold around this race identity, because they're just different people who have a different perspective on life that cannot be predicated based off of class, or gender, or skin color prejudice.”

For me, it was groundbreaking, because I as a Black man would often be like, “Okay, I know this person, I know what's behind this.” Then there was a young man at Hunters Point, dressed all hip-hop style, maybe had a grill, and his question when he sat down was, “What does it feel like to watch someone lose their life?" We were like, “Wow, that's a pretty profound question from a sixteen-year-old.” Typically we just take the questions and we go find someone to answer them, but Chris said, “I'd love to know what's behind that question.” He said, “My mother has epilepsy, and every once in a while she has a seizure, and I'm always wondering, is she gonna pass away? And what will I be? What would it feel like? And then a few weeks ago, I was at the pool with my grandmother, and she fell in. I had to dive in from the other side of the pool, and I had to swim all the way across the pool, and pull her out and make sure she was breathing. Oh my God, I was so scared.” We were like, “Really? Whoa.” We’re thinking, “You’re a young Black male, you think about police violence or community violence, but you’re thinking about your mother and your grandmother. And you can swim.” [laughs] Right? Those kinds of experiences we have very regularly. We’re like, “I'm a total idiot. If I don't know anything about what goes behind the surface of the veneer of a Black male’s experience, who does?” The truth is only that person, if they're even willing to look at that, and even given the opportunity.

The other part about Question Bridge is that when we ask someone a question, like you have done many here, and I'm holding back on mine — it's a generous practice. It's giving someone an opportunity to share their gifts. I overheard someone a few years ago say that givers need takers. This exchange, again, is what I've always been drawn to in all my work, where you have strangers opening themselves up to be vulnerable, to asking a question, and then other strangers answering those questions and making themselves vulnerable, and that being this really magical thing.

YANCEY: It really is magical. I sat down yesterday for half an hour and watched the excerpt you have of Question Bridge online. I didn't move a muscle. It really did make me think that I don't know what a Black man is. I've never seen men answer questions like that, much less seen Black men answer questions like that, and it was really profound to see that level of dialogue. I don't know where that conversation is happening today. It might only be in projects like that, or when things are hard and you need somebody, maybe.

HANK: We really feel like the world needs healing dialogue, it needs methodologies that you're really exploring and sharing, that continue to center the “us.”

YANCEY: That's a nice transition: I wanted to try a little bit of my practice with you in this conversation.

HANK: Alright! How much you gonna charge me?

YANCEY: Well, you could pay me at the end, you could tell me what it's worth to you. So the Bento: there’s the Now Me, what I need right now. Future Me, I think of it as the Obi-Wan me that I’m becoming, a voice that talks back to me. Now Us, the people in my life. Future Us, the world that I want to have happen. In the Bento Society, we do courses and experiences together, and there's one that we do called "How to Read a Room as a Bentoist." The idea is that whenever you walk into a room or a party you want to know who's there. Who do I need to connect to, who should I hit up? But the way a Bentoist reads the room is to know that you walk into that room carrying a lot of different people, and so does everybody else. The way Bentoist might want to introduce themselves is by thinking distinctly about who are all the people in your Now Me, who are all the people in your Future Me, and so on. When we all do that, we find all these other places to connect. Our Now Me’s might have nothing in common, but our Future Us’s are identical. In most conversations, there's very little opportunity to find your way there.

So I thought as a little practice, we could try — you tell me if you're game to do this spur of the moment or if you'd want to write something down — to introduce ourselves to each other through how we would characterize these parts of ourselves. I’ll go first to give you an example.

If I think about my Now Me, the person that's each day doing the work, I think there's a hunter who's providing for his family, who’s always got the eye out. There's a bookworm that's always curious. There's the weirdo that can never fit in. There's an animal that just wants to beast out in a forest somewhere. All of those things are a part of my Now Me at any given moment. Do you have anything that comes alive for you as you think about that question for yourself?

HANK: My Now Me is also a hunter, or a forager, is desperate to be loved, and admired or celebrated for his foraging capacity while also seen as suspect because of the sorcery of it. I'm an alchemist. I’ve referred to myself in the past as a visual culture archaeologist because I’m constantly mining visual and popular culture to bear fruit.

YANCEY: That’s awesome. Nice to meet you, Now Me-Hank. So Now Us: for me my Now Us is my wife and child, my parents. I have two brothers. I’ve got core friends around the world. People I've collaborated with, people I made Kickstarter with. My teachers. Probably more than I would want, but my bullies. And God. God has always been part of my Us. I wonder who you think of as being your Us.

HANK: My Now Us is everyone who has ever lived, everyone who's currently living, and some of the people who will be living after.

YANCEY: So Future Me: the person I'm trying to become, or the person who speaks back to me. I picture my grandfather, who I think of as being a kind person. I imagine a person that looks at me now with the same kind of compassion that I look at my adolescent self with. Someone who's trying to do the best they can with what they know. You could only do so well with the tools you have, and I think about being a person that can truly look at myself and look at others that way.

HANK: My Future Me is still on the path, looking back with a smile. And then looking forward with a long road ahead. This smile is saying, “Look how far you've come. I see you. I see that you're stronger. You're more patient. You're more grateful. And more steady.”

YANCEY: I like your Future Me. So my Future Us: I think about my kid being an adult, making adult decisions, which is terrifying to me on a lot of levels. But I also think optimistically, about a world of abundance, where humanity is a networked organism, something different. I very much feel that Future Us pulling me forward.

HANK: My Future Us is not afraid to hold hands with a grown man in public. My Future Us is proud of the person that I now refer to as my daughter and also is very happy with my wife.

YANCEY: When we walk into a room, these are all the people who are with us. These are people that can have conversations with each other. These are just all pieces that we embody. When I first did this exercise, I had this weird question: Who is guiding this ship? Who is this thing in the middle that's pulling the levers or pressing this button versus that button? How do you think about that? Who's guiding your ship?

HANK: I was introduced through my friend Tony to this idea of another form of AI, which is ancestral intelligence. This connects to the Wide Awakes very much. I see the Wide Awakes — those of us who are in this process of awakening, which you are, clearly, are Wide Awakes. In Buddhism they call us Bodhisattvas. I am very much aware that I am you, and that if we do believe that there is one source, or many sources that are still one, we are here. I am living in your dream world, literally, and you're living in mind. When I think about what's guiding us, it’s all of our ancestors that made all of these decisions, consciously, unconsciously, that brought us to this moment, are guiding us, literally in this moment. Some of them might be the same person.

YANCEY: My last question: I loved your film A Person is More Than Anything Else, which feels like an Adam Curtis movie about the Black experience narrated by James Baldwin. I don't know what you were thinking consciously when making it, but it's amazing. There's a short clip where James Baldwin says something like, he knows what it is what it means to be a Black man in New York. He knows what it means to be a Black man in London. He knows what it means to be a Black man in Paris — seemingly suggesting very different things. After watching Question Bridge I had wanted to ask you what does it feel like to be a Black man. And then after watching that clip, I thought, maybe James Baldwin's way of putting it about how does it feel to be a Black man in different places is more accurate. So what does it feel like to be a Black man in New York? What does it feel like to be a Black man in Nairobi? What does it feel like to be a Black man in America?

HANK: Well, what does it feel like to be a Black man who doesn't believe in race, with brown skin? It feels pretty surreal, right? Because race is someone else's fantasy. It's someone else's fiction. This idea that people are born with these dominant, innate characteristics that dictate by the millions is absurd. It's comical. It's ridiculous, yet and still, it's been so ingrained in me to code these people—even coding you by the wisp in your hair, the thickness of your eyebrows, the tone of your skin in summer. The fact that we are forced to, or have agreed to, navigate a world and play this game that keeps us in opposition with our true natures. When I'm looking out into the world, I do not see a Black man. It's only when people look at me or speak to me and interact with me in ways that show that they have been conditioned to see me, think of me, speak to me, hear me in a certain way, that I'm reminded of this. And the beauty of being able to go to France and go to different parts of the US and go to even Burning Man and go to Nairobi and go to Hong Kong and go to Lima, Peru is that you start to get these different vibrations. It’s not the same. It’s walking through different topography. All of a sudden, my skin color, my texture, my gait means something different. Every country, I can say as a Black American man, feels like a different dimension. In different cities we were like, “Wait, these rules don't apply.” What I found, living in France for a little bit, was — and that's why so many African and Afro-Caribbean immigrants excel in the United States in ways that a lot of African-Americans don’t, is that when you walk out of the forcefield of your societal bubble, you're freer. I wind up places and I'm like, “Oh, wait, I'm not supposed to be here.” It's like, “Oh, wait, are they racist or are they just jerks? I don’t know! But I'm already here.” Whereas those who've been systematically oppressed through the system would never even think to go there.

My practice of liberation, self-liberation, self-emancipation is not just about “Black” people, but it is, especially for me, about European-descended people who I believe have been trapped for the past century in this blob of whiteness, where a hundred years ago, a lot of people we consider white today would not have been white. They would have been ethnic Germans, or Armenians, or Italians. Whiteness in the United States was a way for people to assimilate to be safe. You change your name, you change the way you speak, and you move out of a neighborhood and you move into this kind of amorphous blob that no longer has a culture or an identity, and its sterility is now safe. And so I'm hoping that we can start to embrace, reinvest, and re-engage in all of our complexities. I'm very much inspired by this quote by George Orwell, who says, “Who controls the past controls the future, and who controls the present controls the past.” So if we can build this present, which really is about all of us living in all of our complexities, and bring all the people that are in us, and with us, to every table, maybe then we can start to re-evaluate and take control of this past narrative, so that the future is ours.

YANCEY: Thank you, my friend.

HANK: Thank you.